Over the past few centuries, fashions in facial hair have changed substantially. In the mid seventeenth century many men wore the ‘Van Dyke’ style of a small, pointy beard and moustaches. By the end of the 1600s, beards were in decline, leaving many men with just moustaches. The eighteenth century has been viewed as an entirely ‘beardless age’, and one in which men across Europe abandoned their facial hair amidst new ideas about neat, elegant manly appearance, and smooth faces.

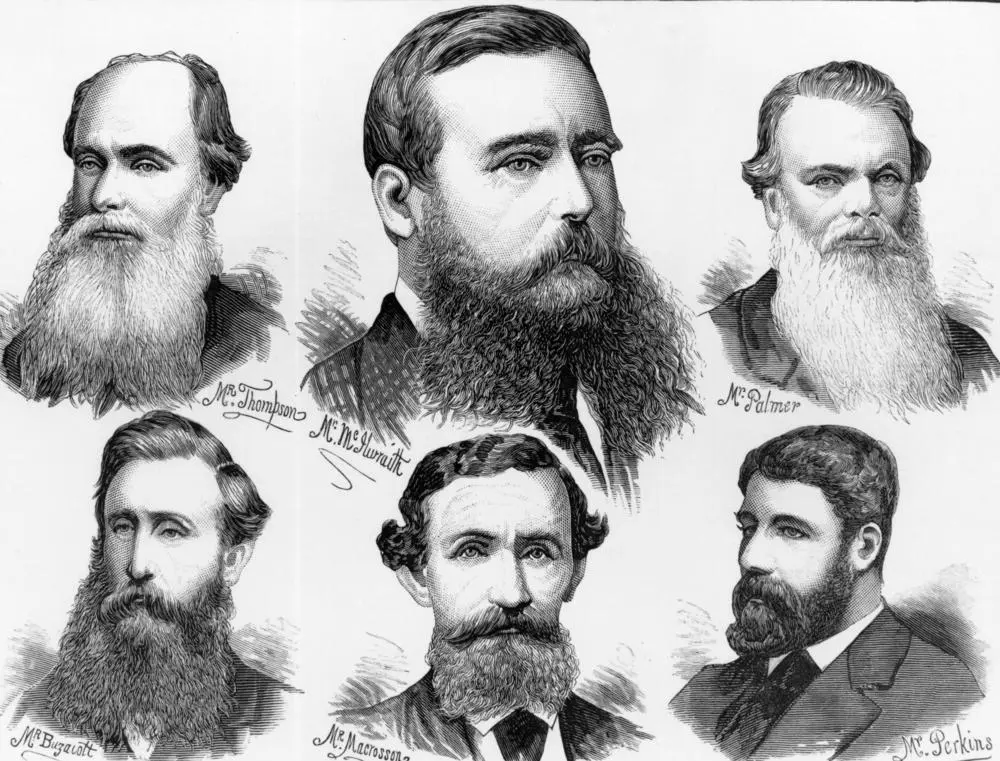

So this remained until around 1800 when a fashion for side-whiskers emerged amongst young elite men in Britain. But beards truly came back with a bang around 1850, amidst the great Victorian ‘beard movement’, when it might appear that men all across Britain suddenly adopted effulgent, luxuriant and magisterial facial hair!

As this chapter in Concerning Beards explores though, there are reasons to believe that these fashions weren’t necessarily as all-encompassing as we might think. Joanne Begiato’s recent book on manliness makes the important point that we sometimes overemphasise stereotypes in the history of masculinity – e.g. the Georgian man of feeling, or the muscularly Christian Victorian man. Whilst these are useful as broad ideals or ideas about manliness, there could be much variation according to thing like class, location and occupation.

In my book, one of the questions that I wanted to explore was how widespread were facial hair fashions at different times and in different places. Did the 18th-century ‘polite’ preference for the clean-shaven face, for example, mean that poorer men had no facial hair either? Equally, whilst proponents of the ‘beard movement’ were expending pints of ink attempting to convince men of the many and various supposed benefits of beards, how far did these ideas sink in?

The problem lies in how to actually get to the faces of men lower down the social scale. Georgian portraits generally reflect elite men, whilst the advent of photography also, at least initially, attracted gentlemen for a sitting. As I found, though, there are ways to tease the faces of lower-class men out of the shadows.

18th-century ‘wanted’ advertisements offered one useful window onto facial appearance. Increasingly, newspapers were used to seek the capture or return of individuals, such as runaway servants, apprentices and criminals. Because those placing advertisements naturally wanted these people caught, their descriptions highlight any distinguishing features. Facial hair was just the sort of thing to be noted. Although a runaway might obviously shave off their facial hair as a means of disguise, the advertisements at least reveal what they were wearing when they took to their heels.

The fragmentary nature of these sources made a large-scale quantitative study impossible, but they suggest that a proportion of men of the eighteenth century did wear some variety of facial hair. In 1763 The burglar Henry Tandy was described as having a large black beard, a dark complexion and ‘pock-fretten’ face. When he deserted from the ninth Regiment of Foot in Bristol in 1756, William Williams had a ‘brown beard and a jolly face’, while the distinctive features of the Edinburgh thief William Brodie included sandy-coloured whiskers ‘frizzed at the sides’.

For the Victorian period, the advent of photography makes it easier to see the actual faces of nineteenth-century men. In particular though, the introduction of photography as a means of recording the faces of criminals offered the perfect opportunity for a bigger study. For the book I surveyed hundreds of photographs of prisoners from three gaols around the country – Bedford, Wandsworth and Carmarthen. Since these photographs were often taken soon after arrest (and before they were likely shaved on admission to prison), they offer a potential glimpse of the facial hair fashions of poorer men.

When we think of Victorian bearded men, we tend to associate them with a particular style – the ‘cathedral’ beard, or ‘patriarch’ beard. But in fact, the findings of my study suggest that a rethink may be needed for the faces of lower-class men…and perhaps even across society. First, across the sample of my study, 58% of prisoners showed some variety of facial hair…which obviously means that more than 40% were completely clean-shaven. Even this raises questions about how widespread across society actually was the beard trend.

Perhaps more surprising was the type of beard that was most common in the sample. Of those men displaying facial hair, across the three gaols, nearly three quarters (72%) had a variation of the ‘chinstrap’ or ‘chin curtain’ beard. This was a line of beard coming down from the sideburns, underneath the chin, and back up the other side, with no moustache. This style could be thin, or bushy, and long or short.

Only 15% of those men with beards wore what we might think of as the archetypal full Victorian beard. Some wore goatee beards, others had light beards or stubble. Only around 3% of prisoners with facial hair wore a moustache on its own. There were also strong variations according to age. Prisoners below the age of 25, for example, often had little or no facial hair. Older men, in their 50s and above, seemed to prefer bushy side whiskers.

Overall, the vast majority of styles in my sample would still require at least part of the face to be regularly shaved. If these findings are in any way representative of the population more generally, the idea of the heavily bearded Victorian gentlemen throwing away his razor and tackle and letting his facial hair run riot seemingly needs revision! Perhaps we shouldn’t even be too surprised to find that individual men made their own decisions about what styles suited them best. Men always have, and still do, retain control over their own facial appearance.

By way of conclusion, it’s worth noting that even contemporaries recognised the wide variety of styles worn by men. In the 1870s, the Hairdresser’s Chronicle noted the ‘countless varieties of forms’ that had arisen in ‘British Whiskers’. It asked the reader to imagine the next few men walking down a busy street.

‘The first has his whiskers tucked into the corner of his mouth , as though he were holding them up with his teeth. The second whisker that we descry has wandered into the middle of the cheek, and there stopped as if it did not know where to go’. The whiskers of number three ‘twist the contrary way, under the owner’s ears’ whereas a fourth citizen, ‘with a vast pacific of a face, has little whiskers, which seemed to have stopped short after two inches of voyage”.

Beards, it seems, just like their wearers, came in all shapes and sizes.