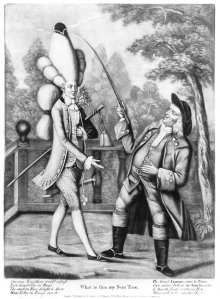

The eighteenth century brought with it a new interest in science and, perhaps more importantly, brought science into the public domain for perhaps the first time. Whereas scientific experiments had once been the domain of dilettante gentlemen, locked away in august institutions such as the Royal Society, more people were becoming aware of just how interesting – and indeed fun –science could be. Public demonstrations were one means through which people could learn about the latest ideas and inventions.

Visitors to the Isaac Newton’s Head public house in London in 1748, for example, could marvel at Francis Watkins’ ‘lately finished and most complete Electrical Machine’. For sixpence they could purchase their own account of all the electrical experiments lately carried out in the Royal Society. In Hart Street, Covent Garden in 1784, amazed onlookers could view marvellous and curious inventions such as the ‘mechanical bird’ of which ‘nothing similar was ever presented in the world’. Mr Cox’s London Museum offered visitors such pleasures as the mechanical machine that played God Save the King.

Alongside this, however, were books of useful knowledge which began to include directions for people to conduct their own experiments. Books of this sort had been around for a long time, often aimed at women and including lots of medical information, along with domestic knowledge, from cleaning pots and pans to directions to make washballs. But the emphasis upon science, and also upon systems of classification, brought diverse types of recipes together, covering everything from medicine and domestic life to experiments designed for no other reason than to entertain onlookers!

One such volume was The British Legacy: or fountain of knowledge, printed in 1754, and which contained ‘upwards of two hundred other curious particulars of the utmost service’ to the ‘Gentleman, the Scholar, the Mechanick and, in a word, every member of society so deeply interested in the Improvement of Arts and Sciences’.

“Besides upward of two hundred Miscellaneous articles of great, nay inestimable value” the reader was promised “the most useful treatise on Farriery ever published”, and well as a ‘certain cure for the Glanders’. What, then, was amongst this panoply of knowledge? Here’s ten items to give a flavour of what the informed Georgian might find useful.

A certain Cure for the most severe flux:

Take a quantity of water cresses and boil them in clear water for fifteen minutes, strain them off, and drink about half a pint of the decoction every now and then, about milk warm.

The flux referred to severe diarrhoea, which was still a common and dangerous problem during this period. Medical remedies for the flux abounded in the early modern period, and belonged to a long tradition of recipe sharing. In fact water cresses can be found in recipe collections for diarrhoea well over a century before this date. Including medical recipes fitted well with the concept of medicine as useful knowledge of the sort it would be useful to keep handy.

To keep arms or any other polish’d metals from Rust:

One ounce of Camphire, two pounds of hog’s lard: dissolve them together and take off the scum; mix as much black lead as will bring them to an Iron colour; rub your Arms &C over with this and let it lie on 24 hours: them clean them with a linen cloth, and they will keep clean many months.

This one might appear strange but, in fact, rusting metal was a constant problem. Before the invention of stainless steel in the later nineteenth century, iron and steel was extremely prone to rusting. Imagine the scene; you’re awoken in the night by housebreakers. You fumble around for your pistol, which has been hanging around for years in a damp room, only to find the mechanism rusted and seized. Keeping metal goods of all sorts polished and rust free was important, and lots of commercial preparations were available to keep iron and steel from rusting.

To destroy and prevent Buggs, and other vermin, by Mr Selberg, Member of the Academy of Sweden:

Mix with the solution of Vitriol, the Pulp of Colquinta, and apply the mixture to all the crevices which serve as a Nursery to vermin; the Solution alone has prov’d effectual; but if apply’d to stone or brick walls, it may be mix’d with lime, which will give it a lively yellow, and insure its success.

Here again, in houses often infected with cockroaches, bedbugs and lice, anything to mitigate the problem was welcomed. The attribution to the eminent Mr Selberg was a common device, often used in medical recipes, to give weight to the provenance and efficacy of the recipe.

Dr Dover’s Excellent Cure for the Itch:

Sweet sublimate one drachm; cream of Tartar one ounce, Let these infuse two or three days in a pint of Spring Water; then bathe the parts broke out therewith, Morning and Evening, for four or five days, and the Cure will be completed.

Another medical remedy here but this time one for the itch – or venereal disease. Whilst promiscuity was certainly frowned upon, there was an acknowledgement that these things happened. It was far less embarrassing to treat yourself from a book than to dangle your putrefying privy parts in front of a physician

Other items appear slightly more perplexing:

To Make Artificial Thunder and Lightning:

Mix a quantity of the spirit of Nitre and Oil of Cloves, the least drop of the former is sufficient; as to Quantity in the latter you need not regard; for, when mixed, a sudden Ferment, with a fine flame, will arise; and sometimes if the Ingredients be very pure and strong, there will be a sudden explosion like the report of a Great Gun.

As an afterthought, the author included the following public health warning!

“It is a little dangerous to the person who undertakes the experiment, for when the effluvia of acid and alkaline bodies meet each other in the air, the fermentation causes such a rarefaction as makes it difficult to breathe for all those who are near it”.

The very next recipe was one ‘To make an artificial earthquake”, which involved 20 ounces of sulphur which, it was promised, after eight or ten hours buried in the ground would ‘Vomit flame and cause the earth to tremble all around the place to a considerable distance”. Don’t try this at home kids!

And one last one that might appeal to anyone who had one of those kids’ science/ chemistry kits that let you grow your own crystals. Ladies and gentleman, straight from the pages of history, I give you…

The Philosophical Tree

Fine silver one ounce; Aqua Fortis and Mercury, each four ounces; in this, dissolve your silver in a vial, put therein a Pint of Water, close your Vial, and you’ll have a curious Tree spring forth in branches which grows daily.