One of the biggest frustrations in studying Welsh medical history is the lack of institutions. In the early modern period Wales was unique amongst the individual nations of the British Isles in having no universities and no medical training facilities. Unlike England, Scotland and Ireland there were no colleges of physicians or surgeons. Why was this? One of the main reasons was the lack of large towns. Wrexham, in north Wales, was by far the largest town in early modern Wales, with a population of around 3500 in 1700. There were many other smaller Welsh towns but, without large populations to cater for, there was no need for practitioners to form trade gilds or corporations.

Over the past few weeks, however, I’ve been turning my attention to the Welsh Marches – the border between England and Wales – and doing some research on large towns such as Shrewsbury and Chester, which were important centres for Welsh people and, it seems, for Welsh practitioners too. One area that I’ve been particularly interested in is that of medical companies and trade guilds. As part of our project in Exeter, we’ve been looking in more detail at the role of barbers and barber surgeons in medicine, both in terms of what they did and how they were described, but also exploring the important question of medical apprenticeships. One company in particular, the Chester Company of Barber Surgeons and Wax and Tallow Chandlers is a particularly rich source of evidence.

The Company were responsible for the regulation of barbers, barber surgeons as well as chandlers who made candles and soap. The relationship between the trades may not immediately be apparent but, in fact, was often interchangeable. People described as barbers were commonly medical practitioners as well as hair cutters and beard trimmers. Barber surgeons often ran barbering shops. The gap between them was extremely fuzzy.

But also, for reasons that are less clear, barbers might also make and sell candles. In the records, barbers can be found referred to as wax chandlers (ie those making wax candles), or as both. Wax candles were relatively expensive since they burned for a long time. Interestingly, however, there appears to be no overlap between barbers and tallow chandlers. Tallow was animal fat, used in candle production. Although tallow candles were cheap, and as bright as wax candles, (around half the price of wax, or less) they burned for only around half the time, so were less effective.

In conjunction with the borough the Company regulated trade and practice, laid out rules for members and also oversaw apprenticeship. Membership bestowed certain rights but also carried responsibilities. Brethren who did not abide by the rules risked censure and fines…and the list of rules was long!

Some orders were routine and concerned attendance and appearance. Every member was expected to attend all meetings unless they had a valid reason, and to wear their gown. They should ‘behave themselves orderly’, not disturb or interrupt meetings and should always call their fellow members by their proper names…on pain of a fine. Other rules related to respect and civility. One brother of the company should not ‘dispraise anothers work’ nor lodge any lawsuit against a fellow member. Neither should they disclose any secrets of their work to lay people, nor give out details of the meetings.

All fees (fines) were to be promptly paid and recorded in the register. These paid for the costs of meetings and food, but also for the burial of departed bretherin. Rule number 14 provided for ‘the decente and comely burial of any of the saide companye departed’ and it was expected that every member should ‘attend the corpse and burial’ unless they had good reason. The fine for non-attendance was a hefty 12 shillings!

Popular culture and religious belief also features strongly. An ‘order against trimming on Sundays’ forbade the cutting of hair on the Sabbath day, again for a fine of 20 shillings. Every year the company also participated in a popular midsummer parade and festival in the city. This involved a procession of decorated carnival floats, and was a throwback to an ancient pagan ceremony. Unusually, it continued long after the Reformation and also survived the Puritan assault on popular revelries. In 1664, an order stated that money should be set out for the stewards to arrange for a small boy (a ‘stripelinge’) to be dressed and ride Abraham, the Company’s horse, in the procession, and to ‘doe their verie best in the setting forth of the saide showe for the better credit of the said societie and company’.

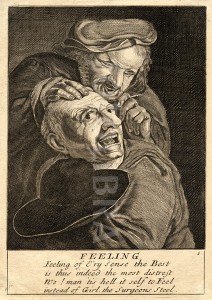

(Left image: public domain; right licensed under Creative Commons-Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.0 Generic)

Perhaps one of the most important aspects of the Company’s function was apprenticeship. The rules of apprenticeship were clearly set out, and this sheds light on a very important and under-researched area of medicine. Only freemen of city, and Company bretherin, were allowed to take on apprentices. Apprenticeships were usually for seven years, but this could vary according to individuals. According to the company rules, no brother should take on another apprentice until his current one was within the last year of his service. The fine for disregarding this rule was a ruinous £10! All apprentices were to be entered into the register or risk a 30 shilling fine.

Why people sent their children to be apprentices in medical professions is not always clear. Medicine was not regarded as a prestigious occupation and, indeed, surgery was sometimes analogous with butchery. Nonetheless an established business in a town could be lucrative, especially given the range of services that barbers provided. As such, the decision to enrol children with urban medics could be pragmatic.

A brief glance at the apprentice registers reveals a number of interesting points. Firstly, it is clear that apprentices were often drawn from a town and its hinterlands. Although some came from further afield, the majority were local or lived within roughly a twenty-mile radius. On 18th Feb 1615 Richard Howe was apprenticed to Edward Wright, barber and wax chandler of Chester, for 8 years. Nicholas Halwood of Chester joined Robert Roberts, Chester tallow chandler for 7 years, while Robert Shone of Broughton’s apprenticeship to a Chester chandler was for 12 years.

In some cases family connections were clearly important, and parents might apprentice their child to a brother, cousin or more distant kin. This was a useful means of drawing on connections to further a career. James Handcocke was apprenticed to his uncle William Handcocke, a barber and wax chandler in September 1613, while Robert Glynne was apprenticed to Richard Glynne to learn the art of barber surgery. Fathers might also take on their own sons as apprentices, a situation that must sometimes have led to fraught relations. Nicholas Cornley was apprenticed to his father Richard for 7 years in 1626, while others such as Robert Thornley, a barber surgeon and painter (!) took their sons to follow in their footsteps.

The conditions in which an apprentice lived and worked depended so much on their masters. While many were well-treated and provided for, which was in fact a central condition of apprenticeship, some masters could be cruel and neglectful of their young charges. Robert Pemberton’s service to Randle Whitbie ended 3 years into his 10-year indenture when he was found to be ‘gone from his service’. John Owen of Cartyd, Denbighshire, ‘ran away before his time ended’ as did Philip Williams, apprentice to Raphe Edge, who took to his heels after a year. Nothing is given as to the circumstances of their treatment; it was not unknown for apprentices to complain of ill treatment, however, and authorities took this seriously. In other cases the stark phrase ‘Mortuus est’ (he is dead) indicates another reason for the termination of an apprenticeship.

The number of entries and records for the company is huge, and will take a concerted programme of research to thoroughly investigate. It will also be interesting to compare these sources with other similar companies across Britain to build up a bigger picture of the activities of medical trades in early modern towns. Once this is done we should have a much broader picture of the role, function and daily activities of medical practitioners in the past.