For this post, I am going to wander into the world of crime in the late eighteenth century, and the grisly fate that befell many who committed the heinous crime of highway robbery. (Full disclosure: I’m not an historian of crime, gibbets or highwaymen…perhaps the case I’m about to discuss is very well known. But he’s new to me, and I love a good story, so he makes it into the blog!)

I was recently reading the The Juvenile Tourist: or Excursions Through Various Parts of the Island of Great Britain, published by John Evans in 1805. Written as letters to a prospective young traveller, it contains descriptions of counties and towns in England and Wales, together with recommendations for tourists for things to see or do. Leafing through the first section detailing departure from London, a particular reference caught my eye.

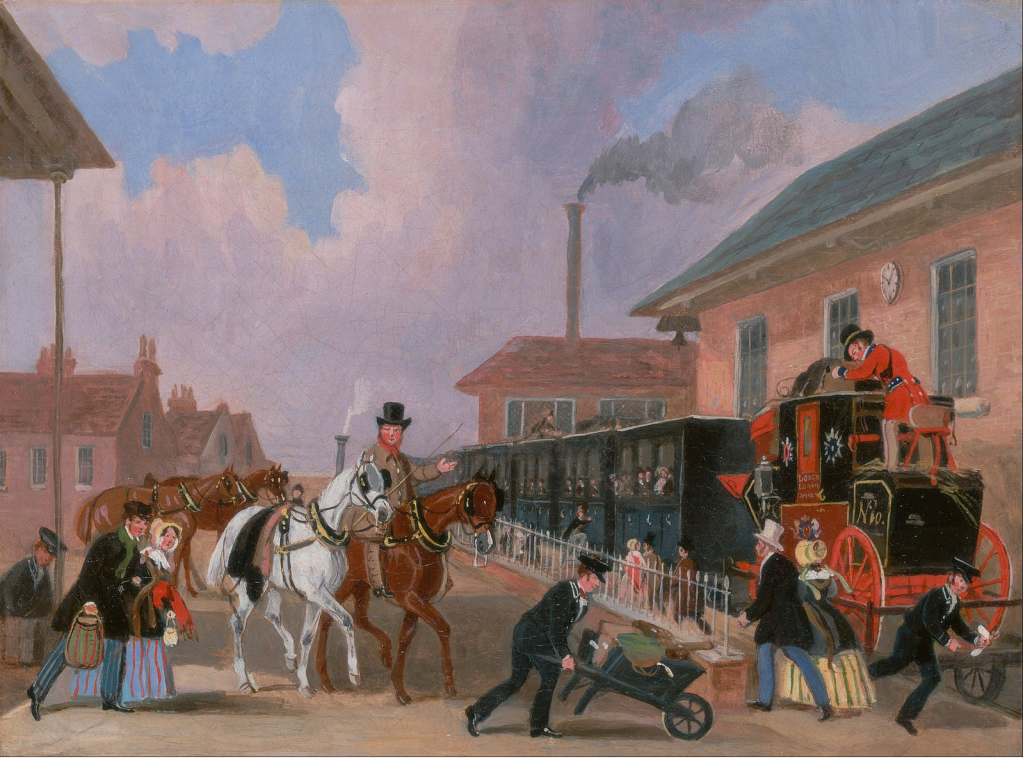

The passage began with a situation familiar to any traveller of this period – a change of horses. Journeys by coach or on horseback were necessarily done in stages. Coaches travelled over fixed distances between two points – usually inns – at which point the horses would be changed. Mounting his new horse, the writer soon continued his journey, heading out on Hounslow Heath. Things quickly took a dark turn though. After pausing at a wooden monument ‘marked with a bloody hand and knife’ marking the spot where a local man who had cut the throats of his wife and child had been buried with a stake through his heart, he moved on to another, equally chilling, relic.

“We still hear not unfrequently of robberies in [this] quarter during the winter season of the year; a recent proof of which is exhibited by a new gibbet, erected not far from Belfont, on which we saw suspended the body of Haines, generally known by the designation of the Wounded Highwayman…”

Who, then, was this mysterious Haines? The problem is that there are potentially many highwaymen Haineses. These include a notable fellow highwayman of the famous Dick Turpin gang, and also one William Haines, sentenced to death in 1783 for highway robbery in Acton, robbing the assistant postmaster of Hackney as he walked home alone through country roads on a dark, foggy December night. While criminal bodies could admittedly be left in gibbets for twenty years or more, becoming more macabre as the years passed and bits and pieces fell off them, 22 years before Evans’ description seemed unlikely.

Professor Sarah Tarlow’s excellent chapter on the afterlife of gibbets (https://rdcu.be/dyItn), however, proved the key to unlocking the identity of the mysterious highwayman. As she reveals, the erection of a gibbet containing Haines’ remains on Hounslow Heath provoked controversy in newspapers, frightened travellers, caused the royal family to avoid the road, and even caused issues when it blew into the garden of a nearby house in a storm. (Anyone who has experienced a neighbour’s trampoline blowing into their garden in a storm should be grateful that it was just this and not a mouldy criminal in a cage!).

The Juvenile Tourist corroborates this, and adds some extra colour. From his description, for example, it is not hard to see how the spectacle of the rotting highwayman might upset delicate constitutions. “He was apparently a large, tall man; his irons were so constructed that his arms hung at some little distance from his body, by which means the hideous sight was rendered more terrific and impressive”.

Clearly no fan of the practice, he noted that Hounslow Heath had once been ‘disgraced with a long range of gibbets’, which had only been removed at the behest of the royal family, fed up with seeing them as they journeyed to and from Windsor. Further Evans noted that the dismal sight of Haines’ body “suggested with full force the horrible idea of a fellow creature deprived of the honours of sepulture” (i.e. burial and memorial) and instead left to rot “to the grinning scorn of public infamy”.

Things start to become clearer from the Old Bailey records, which have lengthy details of John Haines’ trial, and how he ended up in an iron cage by the roadside. In 1799, Haines and an accomplice, armed with ‘certain pistols loaded with leaden bullets’ held up what they thought was a passenger coach. Unfortunately for them it in fact contained two Bow Street officers, and one other man, acting on reports of robberies in the area, and keen to trap a criminal. The trial report suggests that John Haines clearly played his role to the full, wearing a thick brown coat with a hat pulled low, having a distinctive horse and also scoring highly on his highwaymanly patter: witnesses attested to hearing him shout ‘damn your eyes, you bugger, stop and give me your money’!

But what of his nickname, ‘the wounded highwaymen’? A report in the Northampton Mercury provides the last piece of the puzzle. During the robbery there was in fact an exchange of fire. While most of the robbers’ bullets went through the back of the coach seats, one of the officers believed that he “had hit his man”. This was later proved true when witnesses stated that Haines returned to an inn later that night, saying that he had been wounded. When Haines was later arrested “A surgeon described him to have had one ball pass through his shoulder; he had extracted one and he believed there were more in his body”. The ‘wounded highwayman’ was clearly aptly named.

Whoever, he was, and whatever he did, though, there is undoubtedly something disquieting about the image of the desiccated body of the highwayman, the metal locks and hinges of the iron gibbet screaking, and the skirts of his tattered greatcoat waving in the wind!