As we begin to draw near to the end of the Olympics, questions will probably begin to be asked about the ‘legacy’ of the games, and how far they will inspire people to take up sport and exercise. After the 2012 London games, a report noted that 1.4 million more people in Britain had taken up a regular sport since the UK had won its bid to host in 2005. In fact, as the British Olympic team return to the UK next week, the broadcaster ITV and the National Lottery are planning ‘nation’s biggest sports day, the former switching off all of its channels for an hour, to encourage people to follow in the footsteps of Team GB, and take up sports.

(Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Exercise is now deeply entrenched in British culture. Last year the Guardian reported that spending on gym membership was up by 44%, whilst a host of new sports (including open water swimming) along with things like running clubs and organised park runs, was painting a picture of ‘a nation of gym goers’. How many of these new devotees fell by the wayside a couple of weeks after their New Year’s resolution is not, unfortunately, recorded!

We might think of the concept of exercise, and particularly as an aide to health, as a thoroughly modern invention. In fact though, (leaving to one side the original, ancient, Olympic games!) it has a long history.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, for example, the importance of exercise was well known. Popular perceptions of the ‘plague doctors and leeches’ aspect of early modern medicine obscure what was in fact a sophisticated and logical system of understanding the body. Much emphasis is often laid upon ‘weird’ remedies whilst, in reality, prevention was viewed as vastly preferable to cure. A great deal of importance was attached to the concept of ‘regimen’; this was effectively a holistic system for wellbeing, encompassing sleep, rest, eating as well as exercise.

Medical self-help books extolled the virtues of exercise, and in particular motion, as a means to keep the body healthy. Alexander Spraggot’s Treatise of Urine recommended that those in sedentary positions (especially students) needed to keep moving in order to avoid the dangerous settling accumulation of foul humours. Some recommended walking, others riding.

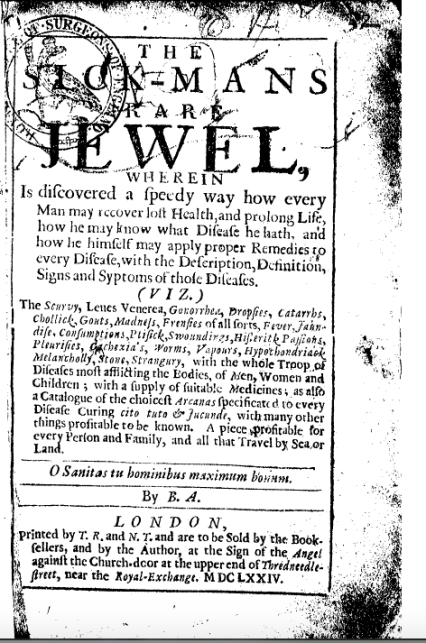

For A.B, author of the 1611 Sick Man’s Jewel, ‘Exercise ought to be moderate, nei|ther too gentle, nor too vehement, neither too quick, nor too slow.’ The activity should be vigorous enough to get the ‘benefit of motion’, to make the face florid and for ‘hot vapours[…] to break forth’. Exercise was considered useful in treating conditions such as Scurvy and diseases of the liver. It also prevented the accumulation of ‘gross, vicious humours, heaped up in the body’. It should never be too vigorous, however, since this could deplete the vital spirits. Neither should exercise be undertaken straight after food.

(image from Google Books)

In 1711 Francis Fuller published an entire book devoted to the ‘power of exercise’. For Fuller, a life spent in lazy, supine repose was dangerous. For the body to be vigorous and vital it needed continual stimulus, ‘since the vigour of the parts is acquir’d by use’. Exercise was therefore vital since it ‘promotes the digestion, raises the spirits, refreshes the mind and strengthens and relieves the whole man’.

But what sorts of exercise was involved? Fuller was vague. ‘By Exercise, then, I understand all that motion or agitation of the Body of what kind ‘soever’. Promisingly, for those who set the bar low, he considered both hiccoughing and laughing as legitimate forms of exercise. The ‘best and noblest of all exercises for a sick person’ was riding. It was both an active and passive exercise, combining movement and the automatic stretching of limbs. For the more energetic, tumbline and rope-dancing offered a good means to get the perspiration flowing.

(Final set tie-break, 17th-century style! Image from Wikimedia commons)

In 1794, in his book on the science of muscular action, John Pugh separated exercise into various degrees. The strongest of these were ‘tennis, cricket, fencing running &c, where great muscular action is necessary’. Next down were activities including walking, riding on horseback or in a carriage and, rather confusingly, reading aloud. In the third category was sailing.

As the eighteenth century progressed, the increasing fixation upon ‘machines’ offered new possibilities for shaping the body. The use of artificial weights was one, perhaps surprising, means by which to exercise. The origin of the term ‘dumbbell’ was actually literal – it referred to the swinging of weights resembling bells with their clappers removed. Philip Jones’ 1788 ‘Essay on Crookedness’ commented on ‘swinging the dumb bells’ as a means to cure spinal distortion and ‘crookedness’. Whilst Jones recognised that some success had been obtained, he was keener on the new trend for sea bathing as a means to keep the body in good order. To promote good posture, the physician James Parkinson advocated exercising with dumb bells, and horse riding. Anticipating 21st century ideas about the healthiness of gardening, however, he also suggested ‘the culture of a flower garden’!

(Copyright Lewis Walpole Digital Image Collection)

Also popular was the ‘chamber horse’ – a chair with a bellows mechanism in which the ‘rider’ sat and then, through the power of the bellows, bounced up and down. For a great post and image of the ‘chamber horse’ on the ‘Two Nerdy History Girls’ blog, click here.

Riding the wave of popularity for ‘gymnastic’ exercise, some enterprising Georgian artisans began to create and patent new equipment. The London merchant Abraham Buzaglo made his name as a maker of patent stoves in the second half of the eighteenth century. But, Buzaglo also used his metallurgical expertise to diversify into other areas. In February 1779 he lodged a patent for a device for ‘Muscular health and strength restoring exercise by the means of machines, instruments and necessaries for practising the same. The apparatus involved a system of plates, bags and poles, attached to the wall, to exercise the limbs. They were especially recommended for the treatment of gout. A contemporary satire depicts the use of ‘gymnastick’ equipment by ‘gouty persons’.

(Copyright Wellcome Images: Three men wearing orthopaedic apparatus, by Paul Sandby)

So as the final events take place in Rio, and perhaps as you lace up your shoes and head for the weights rack, inspired, you’re actually following in the footsteps of health-conscious early modern people, for whom exercise was an important part of health and regimen. It’s interesting to note, for example, the long and close relationship between exercise and health, rather than just recreation. Often the key element has been that of movement or motion. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, motion was needed to prevent an accumulation of foul humours or, in a sense, to prevent the body stagnating. Little has actually changed. The tagline of the Government’s current UKActive programme is… “let’s get moving”!