One of the big themes of my research project, and of a large section of the forthcoming book, is the rise, over time, of shaving as part of men’s self-fashioning and personal grooming. One question that has interested me from the start is that of how men learnt to shave? Who told them what equipment to purchase, how to sharpen razors, make lather and avoid injuring themselves? Fraternal networks – dads and brothers, as well as male friends – were all strong potential sources of information about personal grooming in the past, much as they still are today.

But I’ve also been interested in advice literature for men. The eighteenth century saw the rise of polite conduct literature, instructing young ladies and gentlemen in how to look and behave properly in public. This often included general instructions on dress and appearance, manners, speech and deportment, and even posture and how to stand properly. But before the nineteenth century there was generally more conduct literature available for women than men.

The early decades of the nineteenth century, however, saw conduct literature gradually replaced by a more general kind of advice literature, along the lines of ‘How to be a Lady/Gentleman’. I’ve been scouring as many as I could find to see if they offered anything more on what were sometimes referred to as the ‘toilet arts’! In particular, I wondered if there might be any evidence for how to look after beards, particularly at the height of the Victorian ‘beard movement’. What were the expectations surrounding cleaning, fashioning or cutting facial hair, and general expectations of appearance?

In general, over-attention to appearance was regarded with suspicion, and some advice literature cautioned men not to fuss too much in front of the mirror. As The English Gentleman, His Feelings, His Manners, His Pursuits of 1849 cautioned men that ‘directly you begin to be over-careful and elaborate in your dress, and give yourself a finical and effeminate appearance, from that hour do you commence vulgarity”. Although he should never be slovenly, a man should think no more about his appearance once he had left the dressing room and, once in public, should ‘avoid looking in the mirror’ or a window to check appearance!

Sometimes advice on personal cleanliness could appear in gentlemanly advice literature, although the amount and form varied greatly with each publication. The Gentleman’s Manual of Modern Etiquette (1844) for example, instructed men that the “flesh, teeth and nails should be cleansed at regular intervals”, and the nails in particular should “never be permitted to grow to an offensive length”. Arthur Blenkinsopp’s A Shiling’s Worth of Advice on Manners, Behaviour and Dress (1850) noted also that faces, hair and teeth should be kept scrupulously clean.

One of my favourites is the ominously-titled ‘Don’t: A Manual of Mistakes and Improprieties More or Less Prevalent in Conduct and Speech’ which, as the name suggests, was all about how NOT to do it. Personal grooming was singled out for a barricade of ‘DON’Ts’! These included not using hair dye, since ‘the colour is not like nature, and deceives no one.’ The use of hair oil by men was ‘considered vulgar, and it is certainly not cleanly’. But, perhaps more importantly:

“DON’T neglect personal cleanliness – which is more neglected than careless observers suppose.

DON’T neglect the details of the toilet. Many persons, neat in other particulars, carry blackened fingernails. This is disgusting. DON’T neglect the small hairs that project from the nostrils and grow around the apertures of the ears…”

If men had beards or whiskers they should be careful to wash them after smoking, and should not get into the habit of “pulling your whiskers, adjusting your hair, or otherwise fingering yourself’!

Others contained useful titbits about shaving kit. L.P. Lamont’s Mirror of Beauty (1830) contained a useful recipe for the ‘Genuine Windsor Shaving Soap’, along with instructions as to how to put the melted soap into a shaving box, to use while travelling, or for convenience, whilst Charles Gilman Currier’s The Art of Preserving Health reminded men that the beard ought to be washed very often and should be kept clean.

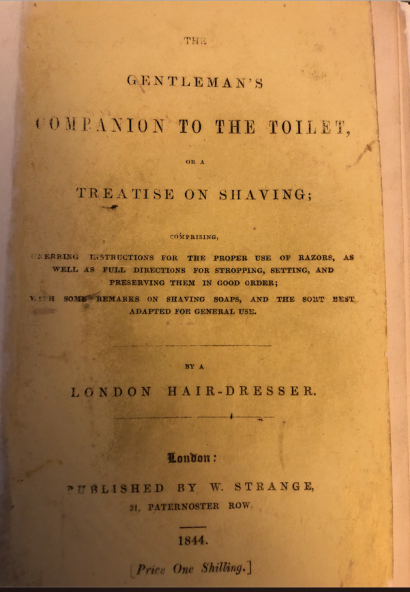

Specific advice about shaving beards and whiskers was more likely to be found in specific publications dedicated to the task. These came in many forms: in the eighteenth century the first shaving manuals were published by cutlers and razor makers such as Jean-Jacques Perret and Benjamin Kingsbury. Over time these began to proliferate, and included everything from instructions given out with shaving products to manuals dedicated to shaving and personal grooming more generally. There are too many to include here in detail, but a few examples will illustrate the themes.

The alluringly titled Gentleman’s Companion to the Toilet of 1844, for example, by the anonymous ‘London Hair Dresser’, contained a raft of useful information for shavers, from how to choose, strop and sharpen a razor, and the proper way to use it. Debates raged around whether shaving with hot or cold water was better: the author of the Gentleman’s Companion was in no doubt that hot water was the only way to ‘soften the beard or improve the edge of the razor’. Another useful section dealt with which shaving soap to pick. The best strategy, argued the author, was to ignored the advertising puffs (“There are many soaps which are ‘puffed off’ as “the best article manufactured for shaving”…but some of them are utterly worthless”). He also advised sticking to the widely available Naples soap, and avoiding alkali soaps, with their light and frothy lather, which would “much annoy you by [causing] those irritating pains which are frequently felt after shaving with a bad razor”.

Edwin Creer’s Popular Treatise on the Hair argued that men risked their health if they neglected cleanliness of their beards, since facial hair “collects dirt, smoke and dust from the atmosphere…and were it not that the beard intercepts those particles, they might otherwise find their way to some internal organ”. Creer also argued that occasional shaving could be useful in strengthening the beard, but preferred to let nature run its course.

Nevertheless, styling, brushing and trimming the beard and whiskers was also recommended. As Creer noted, the ‘cut’ of the beard was everything: it should neither be ‘short and scrubby’ nor long and unkempt. Equally important in preserving the lustre and appearance of a full beard was that it should be well kept. Dedicated ‘whisker brushes’ were available to comb out the tangles and remove errant particles of food. It was, after all, hard to look like a gentleman with bits of dinner lodged in the prolix fronds!

Throughout the nineteenth century, then, gentlemanly grooming was seen as important, and facial hair, whether shaving it off or beautifying the beard, was an important part of this. Perhaps the final word belongs to The Hairdresser’s Chronicle in October 1871, which contained the following, under the title ‘How to Begin the Day:

“Be very careful to attire yourself neatly; ourselves, like our salads, are always the better for a good dressing. Shave unmistakeably before you descend from your room; chins, like oysters, should have their beards taken off before being permitted to go down…”!