Amongst the many impacts of COVID-19 has been the devastation of the travel industry, and its knock-on effects on the global economy. We are all having to think carefully about the ways we travel, not only internationally, but even around our own countries and communities. At the moment, a summer holiday in the sun seems like a long way off.

In Britain, one of the solutions being put in place as we tentatively begin to consider heading out again, is to impose a two-week quarantine on incoming travelers and tourists, in attempts to limit the spread or import of the virus. It all feels very odd in an age where we have become so used to travel that it has become easy, routine and even mundane. But it’s worth remembering that these issues and restrictions are not new, and that the dangers of epidemics have actually shaped travel, and affected individual travelers, for centuries. What was it like to be quarantined in the past? In 1892, a letter was sent to the Coventry Herald newspaper from a Mr W.H. Grant, a traveller to America, who found himself quarantined on a Canadian island in the midst of a deadly outbreak of Typhoid fever.

(Image of a ‘Beaver Line’ ship from WWW.NorwayHeritage.com/Gallery – creative commons licence)

Grant was headed for New York but, due to overcrowding on direct sailings, due to a cholera scare, he elected instead to go on one of the Beaver Line’s ships via Montreal, and finish his journey to NY by rail. Things immediately began to go wrong. The ship he boarded at Liverpool, the ‘SS Lake Huron’, was itself badly overcrowded and ‘taxed to its utmost capacity’, and they departed in bad weather and heavy seas. The ship had not even got as far as New Brighton, in Merseyside, when “a sort of mutiny occurred on board, culminating in a free fight between six or eight of the seamen and officers”. The ship was forced to anchor whilst a tug took the offenders away.

(Image of SS Lake Huron from WWW.NorwayHeritage.com/Gallery – creative commons licence)

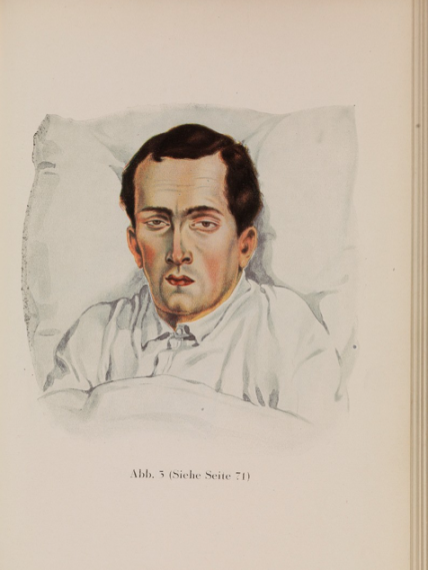

But worse was to come. It rapidly became clear that a serious infectious disease had broken out aboard the ‘Lake Huron’. This was initially “hushed up” and Grant reported that the crew were seen throwing dead bodies overboard with no ceremony when they thought “the act could not be observed by passengers”. When a steward came down with Typhoid fever, it was no longer possible to conceal the truth, and it became clear that the vessel would not be welcomed in port.

(Image ‘Man with Typhoid’ copyright Wellcome Trust, Wellcome Images)

On arrival in Quebec the SS Lake Huron was put into quarantine off an island in the St Lawrence River – “a veritable forest with rocks, valleys, mountains, bays and the most magnificent scenery imaginable”. After two days the passengers were ordered ashore “taking whatever baggage and things we should require” whilst the ship was disinfected. Hopes of a comfortable quarantine looked doubtful though. On landing, all sick passengers were transported to a hospital some distance away, whilst the rest of the passengers were led to clearing in a forest, occupied by whitewashed, one-story buildings, with no locks on the doors, nor separate areas for men and women. They were also dismayed to see nearby a “lonely graveyard in a swamp, where 5420 people were buried twenty-five years ago, within a few months having died of ship fever and cholera”.

With true Victorian efficiency, the passengers of the SS Lake Huron quickly took control of the situation and formed a management committee. Also, true to form though, this was not some egalitarian or Utopian commune, but strictly class divided, with all first- and second-class passengers having their own ‘shed’, subdivided into areas for men and women and children, and those from steerage in another “some distance off”. No need to have the poor near the posh!

Eager to restore some sense of ‘normality’ though, working parties of able men were quickly set up, who rigged up hammocks, cut down trees and even decorated the buildings with ferns and shrubs. Bonfires were made up to cook food, and dinner was served every evening at six o clock by the two cooks from the ship. In this version of ‘lockdown’ passengers soon began to make their own entertainment too. After two days Grant reported that people were busy rambling, exploring, hunting, swimming, and even organizing hill-climbing competitions. A variety of animals were captured including squirrels, snakes and titmice, providing diversion for the youngsters.

The threat of the disease remained, and three families from the steerage buildings were taken to hospital, but after a couple of weeks, Grant was hopeful of returning to the ship and onward to his destination. Here his letter ended, and it is not clear what happened next. (It’s also worth noting that this wasn’t to be the last time this particular ship was quarantined at Quebec: in 1899 an outbreak of smallpox on the ship caused a similar situation.) But whilst the detail and context of his story are unique, they still resonate. Even in unfamiliar circumstances, surrounded by the threat of contagion, and uncertain of the future, people still found a way to preserve some sense of ‘normality’.

(Image ‘Passengers on board ship undergoing quarantine examination, 1883’ copyright Wellcome Trust/Wellcome Images)

And this, without trying to sound glib, is where history IS useful – not necessarily so much in terms of particular approaches or responses, (and hopefully not in terms of the prospects for modern quarantine!) but more in reminding us that what we are experiencing now is not new. The past is strewn with epidemics. We routinely teach children about the Bubonic Plague: our very language is shot through with references to it…e.g. things we should avoid ‘like the plague’. Smallpox. Typhoid. Spanish Flu. Each obviously has its own context, its own effects and symptoms, and each leaves its mark in the collective memory. The important thing to remember, though, is that in time they pass. It might not feel like it at the moment, and the media love their ‘things will never be the same again’ headline-grabbers, but we will come out of the other side of this, hopefully stronger and better prepared for the next one.