Recently I spoke with the Guardian journalist Tim Dowling for an excellent article he was writing (published last week) about whether beards are finally ‘over’, and I thought it would be interesting to reflect on some of this. Since re-emerging around 2014, gaining popularity through celebrity endorsement and a new market for cosmetic beard products and, at least for a time, being celebrated (as well as debated) beards have seldom so popular since the 1960s and 70s. And just when it seemed that facial hair was becoming passé, the pandemic brought a late flourish in the form of the ‘lockdown beard’, with homeworking affording previous beard deniers a chance to try a new look.

Throughout my research on beards, two questions have repeatedly come up, both in media interviews the media, and in questions from audiences at my talks: first has the fashion for beards truly finished, and second what might the next style be? I’ll come on to my answers later, but it’s worth first exploring a bit of context.

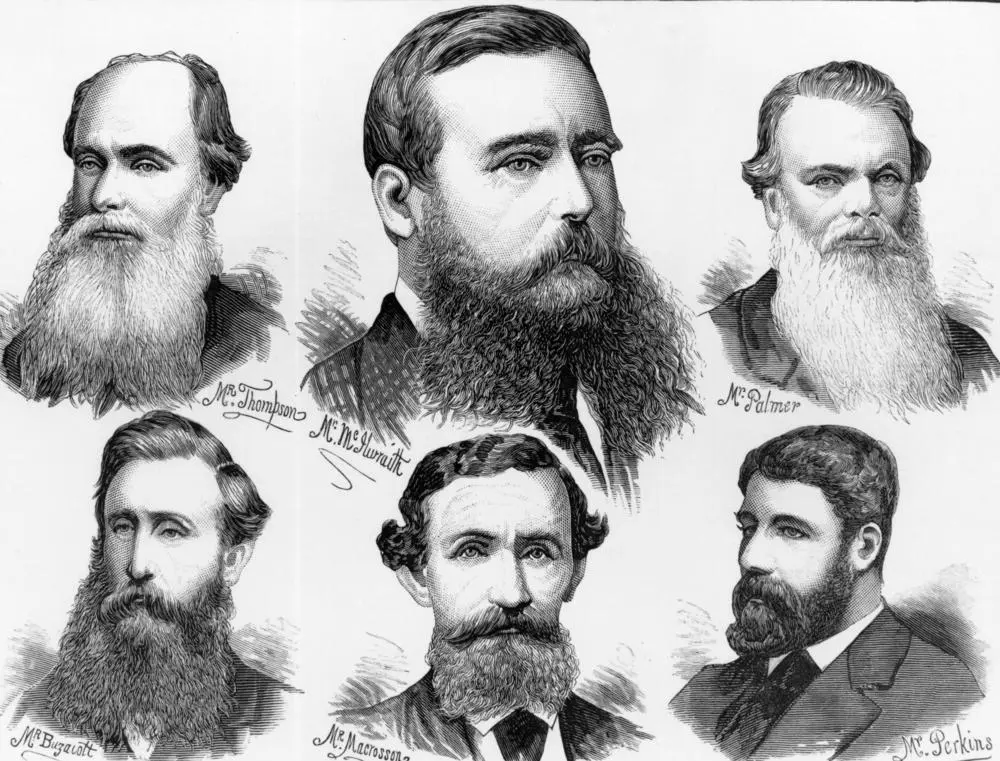

It is important to recognise that facial hair fashions have always been cyclical. More than this, just like clothes, they are sometimes virtually a visual shorthand for a particular period or a historical type. The Tudor men in Holbein’s portraits, for example, are often sporting their magnificent ‘spade beards’; perhaps the most common image of Henry VIII in popular consciousness is that with his characteristic chin beard. In the eighteenth century (as any fule kno!) men were all clean-shaven, and wore wigs, amidst an age of elegant, polite masculinity. If asked to picture Victorian men, however, it’s likely that the prevailing image will be two eyes peeping out between a dense thicket of facial hair and the brim of a stovetop hat.

As broad caricatures these are useful in understanding facial hair trends. But a deeper dive into the records reveals that there is more to this than simple, homogenous trends. In other words, what we assume to be the predominant fashion doesn’t mean that every man wore this style.

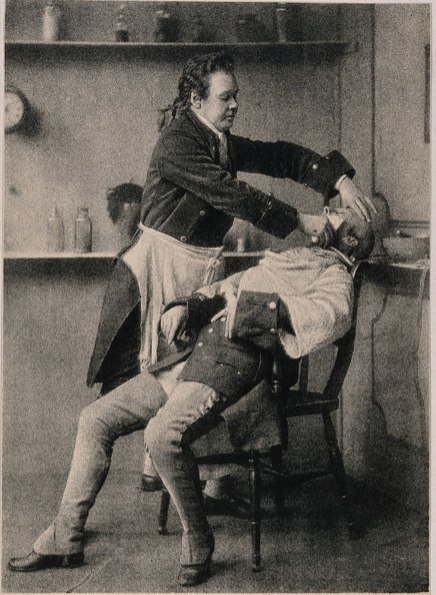

Take the eighteenth century, for example. If portraits are to be believed, then barely a whisker besmirched the face of the Georgian man, except perhaps for very old, the very poor, the ‘insane’, or the religious fanatic. The strictures of polite appearance dictated that facial hair was uncouth, spoiling the general mien of the face, and creating an unfavourable impression for others.

But descriptions of men in ‘wanted’ advertisements for criminals, runaway servants or apprentices reveal a more complex picture, containing many descriptions of men with facial hair of various amounts, styles and colours, suggesting that it might not have been as uncommon as once thought to see men with some form of facial hair. If we assume that these are more likely to be men of the lower classes than elites, then this might even suggest that the clean-shaven model was more applicable to middling and elite men, rather than the ‘ordinary’ guys who perhaps represented the majority.

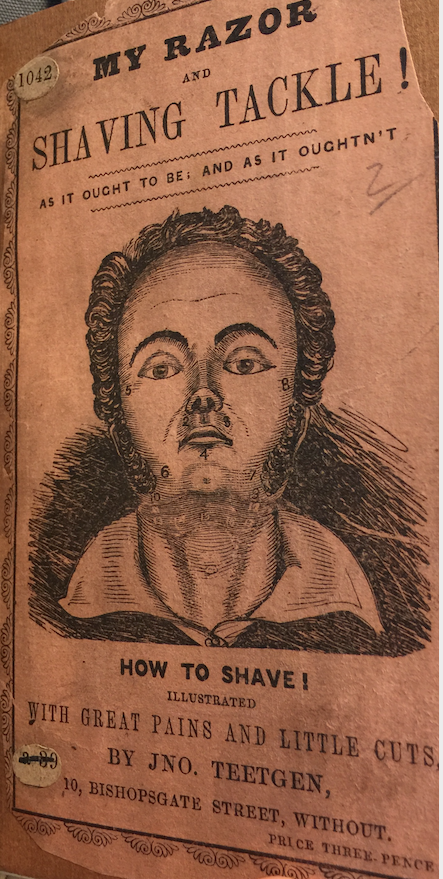

A second point to make is that the frequency of shaving – generally no more than three times a week for elites, and once a week for poorer men – suggesting that the Georgian period was much more a stubbly age than it was a clean-shaven one.

Image: Theodore Lane, The Rival Whiskers, Designed and Etched by Theodore Lane; Engraved by George Hunt (London: 1824)

There were sometimes also counter trends. The early nineteenth century saw a trend for side-whiskers, especially amongst young, metropolitan men, which spanned two decades. Suddenly bushy outcrops of beard, the longer and more elaborate the better, became the height of fashion and, whilst sometimes lampooned in the press, also drew admiration.

For the mid nineteenth century, with its ‘beard movement’, the large numbers of books and articles extolling the many and various supposed health benefits to a fulsome crop of beard, the personal testimonies of men, and indeed the photographic records, all appear to point in the same direction, towards the unassailable dominion of the beard.

But here again, photography, in this case photographs of prisoners taken at the point of arrest, provides a surprising alternative. For my book I compared hundreds of prisoner photographs from across Britain in the 1860s, the supposed high point of the ‘beard movement’ when beard-wearing was assumed as virtually ubiquitous. But rather than the archetypal full beard, these photographs suggested a much wider range of styles. First, it was notable that a substantial number (40% of the 635 sampled) had no facial hair at all. One of the most popular beard styles was the ‘chin beard’ or ‘chin curtain’, a thin strap of beard from the sideburns to under the chin, with no moustache. Goatee beards were popular, as were side whiskers, especially amongst older men. Many younger men were clean shaven, with only a few wearing moustaches. Again, these were men from the lower classes, suggesting possible variations according to social status, but also differences in the choice of styles between men of different ages.

These examples from both periods reveal important truths. First, when we think of beard fashions in the past, we can’t assume that all men, across all of society, adopted the same styles. There were always variations, alternatives, and sometimes reactions. Not all Tudor men had ‘spade’ beards; not all Georgian guys shaved and many Victorians shunned the magisterial fronds of the patriarch! All of this raises a second point, which is that facial hair always involves choices: whether to grow a beard or not; whether to shave or not to shave; whether to grow one style or another, and so on. And, in many respects, as it was in the past, so it is today.

One thing that is certain is that modern beard trends are shorter in duration – a pattern that began in the twentieth century. Whilst broad beard trends once lasted decades…even centuries, they now span periods of several years or even less. But the key point remains the same, that beard fashions, like any other type of fashion, are cyclical. Second, modern beard trends are not homogenous. Even when the recent ‘hipster’ beard trend was in full feather, it belonged to a certain age group and demographic, and large numbers of men (including me!) continued to shave.

Earlier I promised to return to the two all-important questions, so here goes. Do I think the beard is ‘over’? No. In fact I think that something else entirely has happened, which is that it has ceased being a fashion, and is instead now just a style choice, and one that doesn’t necessarily need a ‘trend’ to hang it on. It’s worth noting too that often in the past, when a new beard fashion has emerged, there is an initial period of debate and sometimes ridicule, which settles down as the beard stops being ‘remarkable’.

What comes next? Ah, the all-important one! Historically, beard trends are replaced by their exact opposite, suggesting a return to a clean-shaven model. But, to return to my previous point, I think things are more complicated today, and that any number of facial hair styles are now acceptable. I have seen some magnificent twiddly moustaches and ‘sculpted’ beards in the gentrified coffee shops of Cardiff of late. But one style that has (so far) steadfastly refused to make a comeback are side whiskers…once linked to revolutionary tendencies and angry young men. Might their time be coming?