In October 1663 news spread around London that Queen Catherine was gravely ill. Fussed over by a gaggle of physicians and priests, things got so bad that Her Majesty was even given extreme unction in the expectation that she might not pull through. In an effort to turn things around, as Samuel Pepys noted in his diary on the 19th October, “pigeons were put to her feet”. In another diary entry in 1667, Pepys recorded visiting the dying husband of Kate Joyce who was in his sick bed, his breath rattling in his throat. Despairing (for good reason) for his life his family “did lay pigeons to his feet while I was in the house”.

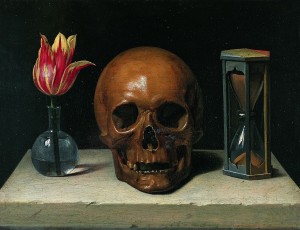

(Image from Wikipedia)

Pigeons? Laid to the feet? Was Pepys mistaken, or was there a misunderstanding of his complicated shorthand? Actually, pigeons were a surprisingly common ‘ingredient’ in medicine and were even recommended for various conditions in the official pharmacopoeia (catalogue) of sanctioned remedies. But what were they used for, and how?

Remedies for the treatment of the plague certainly called for the use of pigeons. No less a publication than the London Pharmocopoeia issued by the College of Physicians in 1618, contained a remedy for the plague which involved pulling off the feathers of living pigeons, holding their bills shut and holding the bare patch to the plague sore “until they die and by this means draw out the poison”.

William Kemp’s 1665 ‘Brief Treatise of the Nature and Cure of the Pestilence’ noted that some writers advised cutting a pigeon open, and applying it (still hot) to the spine of a person afflicted with melancholy, or to a person of weak intellect. The English Huswife of 1615 advised those infected with the plague to try applying hot bricks to the feet and, if this didn’t work, “a live pidgeon cut in two parts”. Even the by-products of pigeons could come in useful. Physicians treating the ailing Charles II applied a plaster to his feet containing pigeon dung.

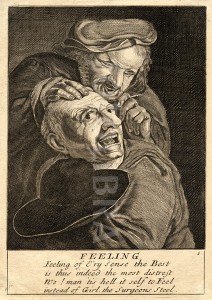

(Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Several sources suggest that the ‘pigeon cure’ was often a remedy of last resort. Writing of the last illness of her father in 1707 (dying of a “broken heart, which the physicians called a feaver”, Alice Thornton reported that, just before his death, pigeons were cut and laid to the soles of his feet. Seeing this her father smiled and said “Are you come to the last remedy? But I shall prevent your skill”. The diarist John Evelyn, in the ‘Life of Mrs Godolphin’ noted that ‘Neither the cupping, nor the pidgeons, those last of remedyes [my emphasis], wrought any effect’.

The ‘cure’ was evidently so popular that it made its way into popular culture, such as in Webster’s ‘Duchess of Malfi’. Speaking to the ‘Old Lady’, the character Bosola says that he would “sooner eate a dead pidgeon, taken from the soles of the feete of one sicke of the plague, than kiss one of you fasting”.

What were the perceived medical benefits of the pigeon and its various products? Some prominent physicians had plenty to say on the matter. William Salmon’s Pharmacopoeia Londonensis, Or the New London Dispensatory in 1716, (p. 200) held that “cut in the middle and laid to the feet, [pigeons] abate the heat of burning fevers, though malignant, and so laid to the Head, takes away Headaches, Frenzy, Melancholy and Madness. On the matter of pigeon dung, Dr Alleyne’s Dispensatory of 1733 stated that “we may judge of the nature of this [dung] from that of the birds…consists of subtle hot parts, which open the pores where it is applied, and by rarifying and expanding them, occasion a greater flux of fluid that way”. In other words the hot dung caused the body to open its pores and expel the bad humours causing the illness.

Saint Gregory (and a pigeon!) – image from Wikimedia Commons

The particular significance of the pigeon is interesting too. One hint is given by the apparently strong connections in folklore between the pigeon and death, ranging from the belief that pigeons flying near a person – or indeed landing on their chimney – were supposed to indicate approaching death, to the “common superstition” (recorded in 1890) that no one can die happy on a bed of pigeon’s feathers. The symbolic power of the pigeon may therefore have been applied in reverse. Killing the bird perhaps imparted its vital power onto the dying person. Beliefs in the power of ‘anima’ – the vital life spirit – being able to be transferred from animals to humans were common in the early modern period.

If some of this seems like it belongs firmly to the 17th century, it is worth mentioning that the ‘pigeon cure’ was still apparently in use in Europe in the 20th century. A fleeting and poignant reference in Notes and Queries refers to a woman in Deptford in 1900, who unsuccessfully attempted to use the cure on her infant son when the medical attendant pronounced that there was no hope for him. He died shortly afterwards of pneumonia.

An article in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1900, though, reported that a Paris physician was casually told by one of his patients that she had “tried the pigeon cure for meningitis”, with some success. The physician, one Dr Legue, expressed his ignorance of the cure, and the patient described it to him.

“The head of the patient to be treated is shaved, and then the breast of the (freshly-killed) pigeon is ripped open by the operator, and the warm and bleeding carcass immediately applied to the bared skull”.

More than this, Dr Legue apparently discovered a shop in the city’s Central Market, where a Madame Michel ran a shop selling nothing but live pigeons, specifically for the purpose of the cure. On interviewing Madam Michel, the good doctor ascertained that she was on the point of retirement after making a “small fortune” from her business, since “the pigeon cure is considered a sovereign remedy for Influenza”, and she had been struggling to keep up with demand. The term ‘sovereign remedy’ takes us straight back to the 17th century but, before the article finished, Madam Michel mentioned one last use for the pigeons. In the case of Typhoid fever, she suggested, two pigeons were necessary. And they should be tied to the soles of the feet.

(Wikimedia Commons)

As uncomfortable as they might sometimes appear to our eyes, early modern medicine involved all manner of plants, animals and substances, alive or dead. Rather than viewing them as ‘weird’, people at the time saw them as valuable ingredients, often with special properties, which they could use to help them in the fight against disease.