As my new project on the history of travel, health risk and preparation begins to get underway, one of the things that I am thinking about is the place of travel within early modern medical remedy culture. What kinds of conditions could befall travellers? What did early modern people think that the processes of travel, and different kinds of transport, could do to their bodies, and what types of remedies were available to deal with them. Research is still at a very early stage, but there are already some interesting hints that remedies were available to treat a variety of travel-related conditions.

Before the broadening of travel in the 18th century, many journeys were relatively short, and local. As a great deal of work has shown in recent years, the early modern population was surprisingly mobile. People travelled from parish to parish, and from rural to urban areas as they visited market towns to buy and sell goods. Perhaps the majority of journeys were taken on foot, on horseback or on a cart or, for those with means, in small carriages. By the later eighteenth century, post carriages were also available to private passengers.

But travel of any kind was a risky business. Roads were proverbially poor, often deeply rutted in summer and reduced to a quagmire in winter, making journeys by foot, or by cart or carriage, uncomfortable at best. Falls from horses were common, leading to injury or death, and even a long time in the saddle could be painful. Travel by sea, even over relatively short distances, was fraught with danger, not only from the vagaries of the weather, but also the condition and seaworthiness of the vessel. Such was the discomfort caused by sea travel that sickness on the first journey by sea was regarded as almost inevitable, only abating once the body had become accustomed to the motion of the waves. With all this in mind, then, what options for treatment could be found in early modern remedy culture?

Travelling of any kind was clearly seen as a tiring and enervating process, and something to which the body needed time to adjust to. Some hints of this process can be found in travel-related terms in dictionaries. The term ‘travel-tainted’ was used by Shakespeare in Henry IV, and was defined by Samuel Johnson as one who was ‘harrassed or fatigued with travel’. To be ‘unwayed’ was to be unused to travel, as opposed to a ‘wayfaring man’ who, according to John Kersey’s 1658 dictionary, was one ‘accustomed to travel in the roads’. The use of the word ‘accustomed’ suggests again a process of acclimatisation. The advice of the Sick Man’s Jewel in 1674 was that ‘such that are weary by travel or labour’ should chew tobacco in the evening, whilst Leonardo Fioravanti recommended the juice of Rose Solis to those ‘who are wearied with travell’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a variety of remedies can be found to treat sore feet. Robert Turner’s, Botanologia the Brittish physician, or, the nature and vertues of English plants advocated anointing feet with the herbs ‘ladies bedstraw or gallium’ before they undertook a journey. There was even a term for this: to ‘surbate’ was to ‘batter the feet with long travel’! Turner noted that the herb mugwort ‘is excellent good to bathe the surbated Feet of Footmen and Lackies in hot weather’, admirably giving some consideration to footsore servants.

For anyone suffering from pain and discomfort caused travelling by horseback, some potential relief could be found. Andrew Boorde’s 1587, The breuiarie of health contained a remedy for galling or chafing caused by ‘riding upon an evill horse in a naughtie saddle’. His suggestion was to ‘rub, anoint or grease the place aggrieved’ with a tallow candle…perhaps not a situation you would wish to walk in on! If the unfortunate chafed traveller possessed a pair of particularly large buttocks, Boorde suggested that rubbing between the cheeks with olive oil might be a useful expedient.

It is harder to trace specific conditions relating to coach travel, but the health dangers of being squashed into a confined space, breathing in the noisome air and odours of fellow passengers, whilst simultaneously being joggled, bumped and bounced around for hours, was a well-known hazard – particularly into the eighteenth century. The term ‘coach sick’ appears occasionally and was regarded as occurring from the ‘swimmings in the head’ that could accompany violent motion. Some physicians advocated opening the windows to constantly refresh the air; others suggested opium!

Whilst sea travel was less common outside naval and commercial purposes, medical authors did offer some suggestions for the alleviation of sea sickness. In his 1667 Treasures of Physick, John Tanner viewed sea travel as one of the key ‘external’ causes of vomiting and advocated a range of treatments including laudanum, vegetable and herbal oils and syrups. As John Moyle noted, in his 1684 Abstract of sea chirurgery, it was not uncommon for the abject misery of constant puking to be accompanied by the discomfort of constipation: he claimed to have ‘known some who in a whole week together have not gone to stool’. Moyle’s solution for those who were ‘sea sick and vomit much’ was a gentle purge or, failing that, a ‘clyster’, or enema.

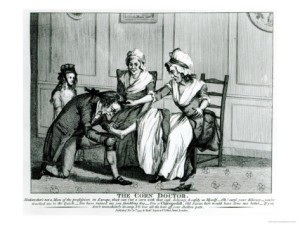

As ever in the early modern medical marketplace, where there was demand there was likely a crafty quack chasing a fast shilling. Travel-related conditions were common amongst the efficacy puffs for proprietary pills and medicines. In 1670 the ‘English Pills for the Scurvy’ claimed to be extremely useful for sea travellers, standing them ‘in great stead in all Sea-sicknesses’, as well as ‘sickly Climates or Seasons; Calentures, Fevers, Fluxes, Poysons, Agues, Surfeits, and the like Scorbutick Diseases, which so commonly afflict such as go to Sea’. John Archer’s ‘Chymical Drops’ were of ‘great use to travellers’ in curing sickness, whilst ‘he that useth [John Headrich’s Traveller’s Salt] on the Sea Vomits not’. There are many more similar examples, and plenty more still to find.

Health and medicine were, as they still are, then, central to travel. Even the few examples given here are revealing about the supposed effects that travel was seen to have on the body, along with the approaches taken to mitigate them. I am very much looking forward to delving more deeply into the medical history of the travelling body.