“There are few diseases which afflict the Human Body, attended with greater disadvantages, than those produced by Distortion. It gives not only an unpleasing appearance, but innumerable complaints generally follow”. So ran an advertisement titled ‘Distortion’ in the True Briton newspaper of January 1800.

In the eighteenth century, good posture was becoming an important issue. Sloppy posture which, in John Weaver’s Anatomical and Mechanical Lectures Upon Dancing (!), included ‘holding down the head’, putting out the chin, stooping in the shoulders, bending too much forwards and thrusting out the belly’, were not good signs. The vagaries of early modern life left their mark on the human form in various ways. Various medical conditions could leave bodies in a far worse state than they found them. Diseases in childhood, such as rickets, affected gait, while accidents could lead to poorly formed limbs. Well-meaning but botched medical interventions could leave highly visible traces. Poor diet and harsh living conditions affected health and appearance. In all respects the eighteenth-century body was a product of its time.

A ‘crooked’ body left its owner open to a cruel raillery of insults. David Turner’s excellent book on disability in the eighteenth century details some of the terms of ridicule that could be levelled at those whose bodies did not conform to erect ideals.James Caulfield’s 1793 dictionary of slang included terms such as ‘lord and lady’ to denote a ‘crooked or hump back’d person’. A ‘lame or limping man’ might be referred to as ‘Mr Hopkins or Hopping Giles’. In literature, ‘deformed’ people were treated to highly pejorative terminology from ‘a creeping creature’ to various other plays upon ‘crookedness’, lameness or distortion. Having a ‘crooked’ body could also be a potential social barrier. For a woman marital prospects could be hampered. For men, the emphasis upon hardy male traits such as elegance of form and posture – as well as a general mien – made standing up straight a key consideration.

But, as with many other areas of daily life in the eighteenth century, where there was a problem, there lurked a ‘specialist’ to sell you something for it. Georgian newspapers contained a raft of devices designed to help people shape their own bodies. Key to this process were conceptions of ‘correction’ and ‘concealment’. One of the biggest areas of the market was for devices to ‘cure’ hernias. In many ways the eighteenth century was a golden age for the ‘rupture’. New types of industrial processes, the harsh, physical nature of manual labour and even the demands of new environments such as the navy led to a virtual plague of ruptures. The problem with inguinal hernias was the fact that they could lead to large, painful and highly visible swellings in the groin. No surprise then that truss makers often sought to emphasise the strength of their products in concealing the problem.

In 1790, Mr Dowling “Improved Patent Elastic Truss Maker’ of St Martin’s Lane, London, begged leave to acquaint the public that he had brought his trusses to ‘so great a degree of perfection that the most troublesome rupture can be kept up with ease and safety’. Unlike tight waistbands which worked by ‘forcing the contents of the abdomen downwards’, making them uncomfortable to the wearer, Dowling’s ‘Improved Elastic Breeches Straps’ were just the ticket to keep everything held up and in place. Timothy Sheldrake’s ‘Double Springed Elastic Truss’ was claimed to ‘keep the largest rupture up with less inconvenience than a small one can be kept up with any other Truss’.

An important consideration for wearers was that of discretion. To be seen wearing an unwieldy truss would merely draw attention to the afflicted parts. As ever, makers were ready. J. Meares of Ludgate Hill reassured customers that his devices were so discrete that ‘even the most intimate companion cannot discover it’. Others designed their products to be ‘indistinguishable from nature’.

Apart from trusses, a range of products was available to encourage the body into a straight, erect form. It was seen as important to catch children early and teach them (by means of forcing them!) to stand properly. Leg irons, to be found amongst the stock of J. Eddy of Soho, were one means of forcing bandy legs into a socially-pleasing form. ‘Elastic bandages’ and stays worn under the garments used their properties to force an errant body into submission. As children got older and went to school, the process accelerated. Parents of girls were especially obsessed with achieving the graceful swanlike neck so desired by artists such as Joshua Reynolds and his ‘serpentine line’. Amongst the products for achieving this were steel collars, that literally forced the chin up into the air. Steel ‘backs’ and ‘monitors’ were strapped to the back and made it next to impossible for a young person to slouch. Exercising with ‘gymnastick’ equipment including dumb bells was advocated to open up the chest. In 1779, one Abraham Buzaglo patented his ‘machines &c for gymnastick exercises’.

Many of these devices were extremely uncomfortable to the wearer. The Reverend Joseph Greene complained that his truss chafed the sensitive skin of his inner thighs and ‘bruis’d ye contiguous parts’. Writing in 1780, Henry Manning commented on the popularity of such devices, which, he argued, were of little practical help. Indeed, according to Manning, the patient frequently became unhealthy and died in an exhausted state, or was forced to live out a miserable existence confined to chair or bed! Makers were forced to respond by stressing how light, durable and comfortable were their products. J. Sleath was at pains to reassure ladies that his steel backs and collars ‘of entire steel’ were ‘peculiarly light, neat and durable’!

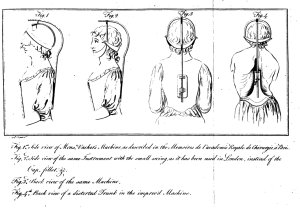

By far one of the most painful devices ever marketed was the ‘neck swing’. Swinging was recommended by surgeons as a means of stretching the spine. The ‘neck swing’ operated by encasing the sufferer’s head in a steel cap and frame, by which they were suspended off the ground for hours at a time. A surviving account by a young English girl highlights how uncomfortable this could be.

“I remained suspended in a neck swing, which is merely a tackle and pulley fixed to the ceiling of the room; the pulley is hooked to the head-piece of the collar, and the whole person raised so that the toes only touch the ground” In this position, she spent much of the day. After two decades of treatment, it was reported that her spine had actually decreased by six inches!

People were prepared to go to great lengths to achieve a straight body, even if it meant enduring excruciating pain to do it. The eighteenth century was indeed a period when people were increasing turning to new technologies in order to shape their own bodies, from razors and personal grooming instruments to postural devices and even new types of surgical instrument. Today we still have a strong sense of ‘straightness’ as a bodily ideal and a large market exists for products to help us sit straight, particularly in the workplace. Whilst the ‘neck swing’ may have long gone, we’re still obsessed with body shape and the need to conform to what any given society deems to be ideal.