Posture is a problematic issue for medicine. Having established a link between ‘bad’ posture and all manner of conditions, from spinal curvature and back pain to nerve damage and headaches, slouching is high on the government’s hit list. Why? Let’s be clear about it, back pain is as much an economic issue as a medical one. While clearly there are many causes for back pain, the BBC recently calculated that it costs the NHS over £1.3 million every day. Add to that the costs to businesses of lost working time and it is painful to the economy as well as the body. It is no coincidence that the NHS website has a number of micro-sites dedicated to suggestions for improving the way we sit and stand.

All manner of devices can be bought with the aim of straightening us up. Leaf through the pages of those glossy little free catalogues that often appear in the post (the ones which routinely have walk-in baths, shooting sticks and things for kneeling on in the garden…you get the picture?) and you’ll notice a panoply of postural devices. There are corsets to force you back into position, as well as all manner of back braces to pull your shoulders back. You can buy cushions for your favourite chair that encourage you to sit in a ‘better’ (for which read less comfortable!) way, as well as special chairs that encourage you to kneel. Even, recently, desks that you stand at, instead of slumping in front of the PC screen. All tested. All clinically proven. All, usually, very expensive. Someone is making money off our drooping shoulders and crooked spines.

But devices to make us sit or stand ‘straight’ are certainly nothing new. As we’ll see, the Stuarts and Georgians got there first with a variety of more or less painful solutions. What have changed are attitudes towards posture. For the Georgians, posture was partly medical, certainly, but perhaps more of a social and cultural issue. Put another way, the ‘polite’ body stood straight and tall; to hunch over was unnatural and uncouth.

In the eighteenth century, the ideal body was straight and well proportioned. But even a cursory glance around the inhabitants of a Georgian town would confirm that many – perhaps the majority – were very far from this ideal. Vitamin deficiency caused by poor diet stunted growth, while a variety of diseases experienced through life could leave their mark. Accidents and bone-breakages might be cursorily treated, but a broken leg could easily leave a person with a limp. Also, many conditions, which today are easily treatable, were then left to run rampant through the body. All this meant that the ‘standard’ Georgian body was often far from the ideal.

It would be easy to assume that people simply accepted their lot and got on with their lives. Doubtless many did. But the eighteenth century also witnessed an increasing willingness to shape the body to try and bring it more in line with this elusive ideal. In 1741, Nicholas Andry published his famous ‘orthopedia’, in which he likened the human body to a tree, which needed support as it grew and, later, as it declined. His famous image of the so-called ‘Tree of Andry’ illustrates this well.

The eighteenth century was a golden age of corrective devices. Just like today you could buy a vast number of corsets and stays, which aimed not only to correct medical deformities, like ruptures, but to help women to try and meet the most fashionable body shape, of a miniscule waist and broad bust. The experience of wearing some of these devices must have been at best uncomfortable and, at worst, excruciating.

There were, for example, steel ‘backs’ – large plates of metal inserted and lashed inside the back of the wearer’s clothing, which ‘encouraged’ them to stop slouching. Metal ‘stays’ gave the illusion of a harmonious form while simultaneously forcing the sufferer’s body back into a ‘natural’ shape. Here’s a typical advert from an eighteenth-century newspaper showing the range of available goods:

“London Daily Post and General Advertiser, February 16th, 1739

‘This is to give NOTICE

THAT the Widow of SAMUEL JOHNSON, late of Little Britain, Near West Smithfield, London, carries on the Business of making Steel Springs, and all other Kinds of Trusses, Collars, Neck Swings, Steel-Bodice, polish’d Steel-Backs, with various Instruments for the Lame, Weak or Crooked.

N.B. She attends the Female Sex herself”

Perhaps some of the most uncomfortable devices were those to correct deformities of the neck. For both sexes, having a straight neck was extremely desirable. For men, keeping the chin up was a sign of masculine strength, poise and posture. Those who slouched were mumbling weaklings, destined never to get on in business or the social sphere. The allure of the soft female neck, by contrast, lay in its swan-like grace; a crooked neck ruined the allusion of femininity and threatened the chances of a good match.

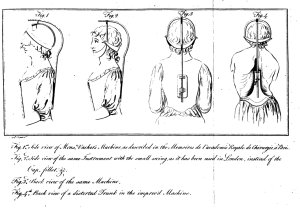

Many makers supplied products to help sufferers of neck problems. Metal collars, hidden under clothing, forced the chin up. If it sagged, it would rest on an uncomfortably hard metallic edge. Perhaps the most extreme of these devices, however, was the ‘neck-swing’ supposedly introduced into England from France by one ‘Monsieur Le Vacher’. This heavy apparatus fitted around, and supported, the wearer’s head and neck, after which they were suspended, feet off the ground, in an effort to elongate the spine and promote a straighter back. We have one unique testimony of someone who tried it. She described how, every morning, she was: “suspended in a neck- swing, which is merely a tackle and pulley fixed to the ceiling of the room; the pulley is hooked to the head-piece of the collar, and the whole person raised so that the toes only touch the ground”. In this awkward position she remained, sometimes for long periods of time.

There seemed to be something of a vogue for postural devices in the eighteenth century, to the extent that they even entered popular culture. In the anonymous Village Memoirs: In a Series of Letters Between a Clergyman and his Family in the Country, and his Son in Town, the titular clergyman noted the vagaries of bodily fashions: “To remedy the ill effects of a Straight line, an uniform curve is now adopted – but alteration is not always improvement – and it reminds me of the conduct of the matron, who, to prevent her daughter from dropping her chin into her bosom, threw it up into the air by the aid of a steel collar – Hogarth’s Analysis has as yet been read to very little purpose’

It is therefore interesting to note how the dialogue of posture has changed over time. Georgian postural devices sought to return the body to a state of nature, or meet an ideal of appearance. While they certainly encouraged the returning of sufferers to productivity, this was less important than creating the impression of a harmonious whole. Today it might be argued to be the other way around. While cosmetic appearance is undoubtedly important, the emphasis is firmly upon health and minimizing the pressure on a creaking health servce. Our impressions of the body rarely remain static. How will the bodily ‘ideal’ translate itself in future?

great site and information!

Thank you very much – really glad you like it

Reblogged this on Dr Alun Withey and commented:

One from the archives: a post about bad posture and treatment in the 18th century