After more than seven years of work, hundreds of sources, and a major research research project, I’m very proud to be able to introduce my new book Concerning Beards: Facial Hair, Health and Practice in England, 1650-1900. It’s a proud day and always a thrill to finally have the first physical copy in my hand…It always seems hard to believe, when writing the very first lines for the first chapter that it will ever add up to a book! In this post I thought it might be nice to say a little about the book, some of its main themes and findings. In the coming weeks I’ll be posting more about some of the fantastic material that I’ve come across through the project.

At its heart, Concerning Beards is all about the relationship between facial hair, health and medicine between the mid seventeenth and late nineteenth centuries. Why, first, does it have this timespan? First, it spans a period which saw some major changes in fashions and attitudes towards facial hair. In 1650 beards and moustaches were still in fashion, but were in a gradual decline. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, amidst changes in ideas about politeness, sensibility and a more refined model of male appearance, facial hair fell from fashion, and it has been assumed that men were largely clean shaven for the better part of the next 150 years. Then, around 1850, the Victorian ‘beard movement’ saw beards held up as an important, and highly visible, symbol of manliness. The book, therefore, covers a long period in which facial hair was initially in fashion, suffered a long decline, and then came back again with a flourish!

Second, the long timespan covers an interesting period in terms of medicine and the body. In the seventeenth century, and throughout much of the eighteenth, the body was still believed to consist of four humours, which governed health and temperament. Within this system, beard hair was regarded as a type of bodily waste product, or excrement, that was left over from the production of sperm deep within a man’s body. As such, facial hair was seen as internal substance, and one that was firmly linked to male sexuality, virility and physicality.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, however, beliefs in the humours were being gradually eroded, and older ideas replaced. Facial hair was a part of this and, by the mid eighteenth century, it was more common to find debates about facial hair focussing on things like the structure of beard hairs and how they grew. Increasingly beard hairs were seen as growing on, or just under, the skin, rather than deep in the body. As this happened, the older links between beards and sexual power gradually disappeared.

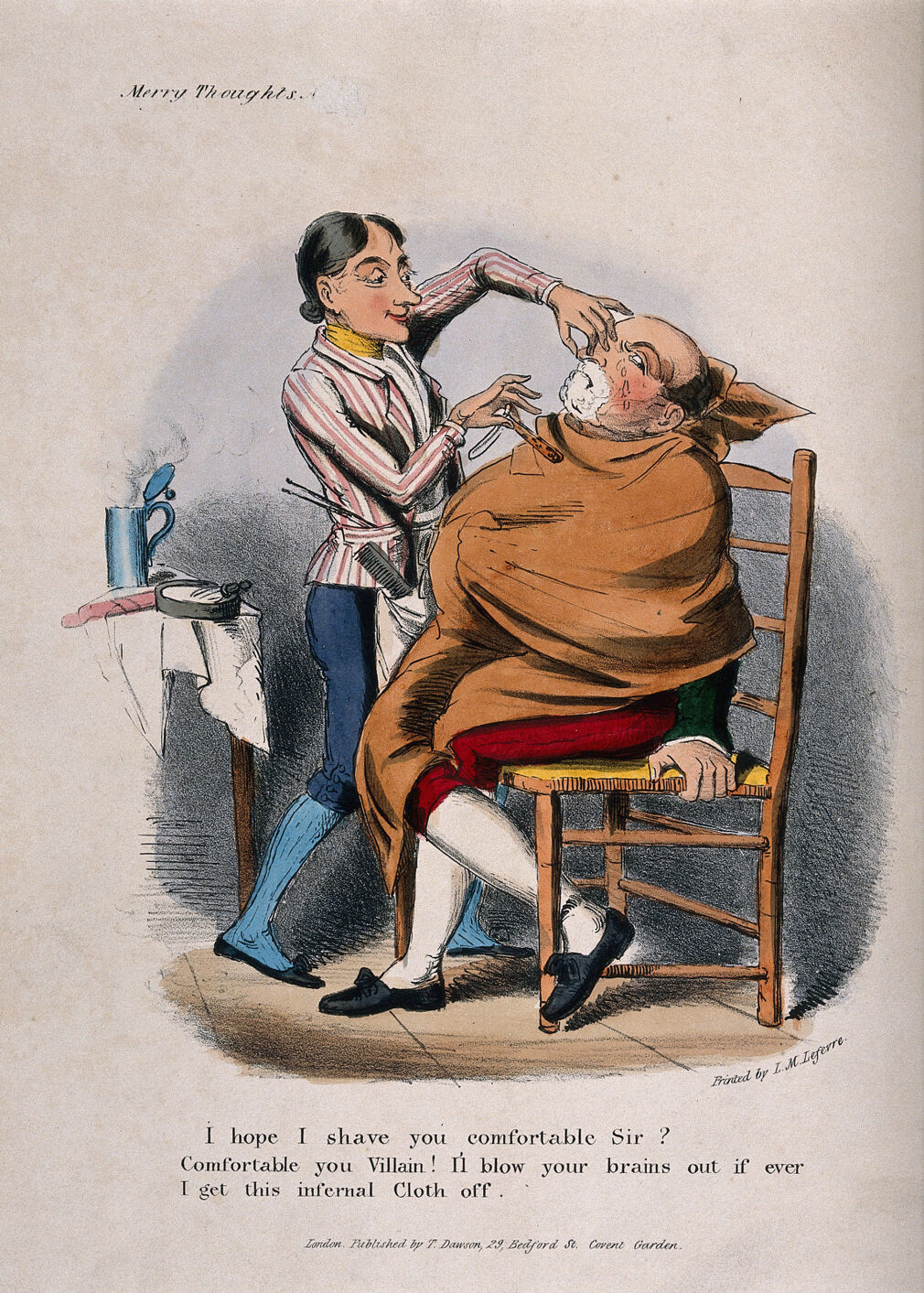

Over the course of this time period, other things changed. One was certainly who was responsible for shaving. In the early modern period, aside from a few elites who dabbled with wielding a razor, the barber/barber-surgeon was the mainstay of shaving. Barbers were incredibly important figures for men, and their shops were places where men could go to gossip, drink, gamble and play music, as well as have their beards and locks trimmed.

From the later eighteenth century, however, men certainly began to shave themselves more, helped on by the availability of new types of steel razor, and a growing body of advice literature telling them how to do it. In 1745 too, the barbers and surgeons split to form separate companies, which has long been assumed to have sent them into a social spiral. But my book argues that this didn’t actually happen, and that barbers remained hugely important. In fact, even at the height of the ‘beard movement’ when huge numbers of men were wearing full beards, barbers were actually experiencing huge demand from working men, which at times found them having to work through the night to cope with the sea of stubbly faces at their doors.

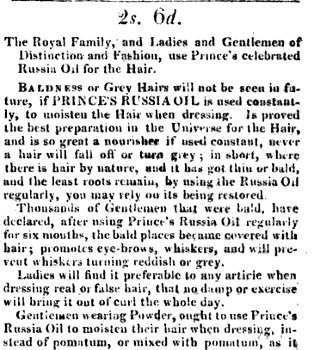

Another key question that the book addresses is that of the rise of a market for cosmetic shaving products. It argues that, over time, managing facial hair gradually lost its associations with formal medicine and medical practitioners, and became instead part of a new category of personal grooming for men. But even despite this, it still remained (and in fact remains today) closely linked to hygiene and health.

From the later eighteenth century, a whole new market emerged for shaving soaps, pastes, powders and creams. For the book I surveyed thousands of advertisements, exploring the types of products available, names, prices and also the language used to advertise them. I’ll save the details for a later post, but things like scent, and the language of softness, luxury and sensuousness, raise interesting questions about expectations of manly appearance and behaviours.

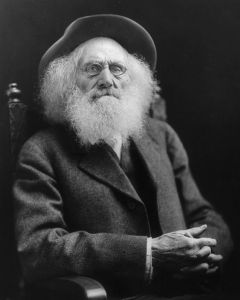

Finally, although the book is not centrally about fashions, it does discuss questions of facial hair styles and class. As Joanne Begiato’s recent book on 19th-century masculinity has argued, the temptation has too often been to separate broad time periods into different ‘types’ of manliness: e.g. the Georgian polite gentleman, the Victorian ‘muscular Christian’ and so on. But how far do those models of manliness reflect men across society and in different locations? In terms of beard fashions, is it safe to assume that, for example, all men in the Georgian period were clean shaven, or that all Victorian men wore prodigious facial hair. The problem lies in how to access the facial hair fashions of the lower orders.

For the eighteenth century I turned to ‘wanted’ advertisements in newspapers, where runaway apprentices, servants and criminals were commonly placed. Since facial hair was a distinguishing feature, it offers a glimpse of what men looked like, at least at the point at which they had taken to their heels. This study suggested that beards actually were quite rare throughout the eighteenth century, but that whiskers were perhaps much more common. Rather than all being clean shaven, many lower class eighteenth-century men likely had some sort of facial hair.

For the nineteenth century, though, I was able to turn to actual photographs of lower-class men, through the increasing practice of taking photographs of prisoners. For the book I surveyed hundreds of photographs from gaols around the country, taking note of the style of facial hair, the age of the men, occupation and location. What this revealed was actually quite surprising. At a time when the ‘beard movement’ was at its height, and it has been supposed that the majority of men were wearing huge, full beards, the study of prisoner photographs suggested not only that around a third of men had no facial hair at all, but that the full beard was not the most popular. In fact, remarkably, the vast majority of men in the sample would have needed to keep shaving at least part of their faces.

Along the way, Concerning Beards covers a wide range of other questions, and has turned up a great deal of interesting titbits! How did apprentice barbers learn to shave, for example, and who taught individual men? What sorts of things did barbers sell in their shops? Why were some men in institutions physically compelled to shave? And why was Tom Tomlinson the barber, completely unsuited to his calling? For the answers to these, please have a wander through the chapters.

So here it is, and I’ve saved the best until last. Thanks to the generosity of the Wellcome Trust, both in funding the project, and funding Open Access, Concerning Beards is completely free to download. Please click the link below to Bloombsury Collections, where you can find all chapters available to download as PDFs.