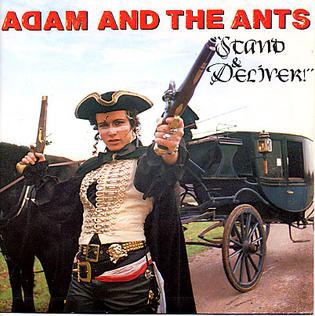

I’m showing my age now, but watch the 1981 Adam and the Ants promo video for ‘Stand and Deliver’ and, during a few scenes showing the ‘Dandy Highwaymen’ amongst a group of outlandishly-dressed Georgians, look closely and you may notice a strange figure in the background…a man wearing a powdered period wig…and a beard. A wig and a beard. Together. On one man. It’s a look that should never be seen on any man. And, indeed, it was likely not a combination worn by any self-respecting polite Georgian gentleman. As the wig grew in popularity, the beard dramatically declined.

Initially there had been objections to the wig on religious grounds. In the seventeenth century, Puritan objections to the beard centred upon meddling with the divine form that God had created. The puritan polemicist William Prynne argued that replacing an individual’s own hair with the ‘hairie excrements of some other person’ was akin to denying the perfection of God’s work. Here he was referring to the fact that hair was, in medical terms, regarded as a type of excrement – a waste product of the body caused by inner heat rising up and breaking out on the surface of the skin, much like soot up a chimney. But clean-shaven puritans clearly saw no irony in the fact that they had removed their own ‘hairie excrements’ in the form of the beard which God had presumably provided for them.

There were also tensions in religious tracts between notions of the wig as, on the one hand, a covering and, on the other, a form of display. The wig-wearer could simultaneously be accused of hiding their true features, and drawing unnecessary attention to themselves. Contemporary opponents to the wig also claimed that it altered gender perceptions of the body, confusing the appearance of the whole. Even despite these objections, wigs continued to go from strength to strength.

Hair, whether on the head or the face, was in fact a central component in the articulation of masculinity. The way that head hair was worn and styled was important. At some points, long hair was desirable but, at others, it was kept short and close cropped. Here again, Puritans were advocates of the short cut. The wig added an extra layer of complexity, in requiring the removal of the wearer’s own hair, and substituting it for the ‘dead’ hair of someone else.

Like head hair, fashions in beards waxed and waned throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The beard was considered a central component of manliness, one that demonstrated virility and manly vigour. The bigger the beard the better. By the last decades of the seventeenth century, though, facial hair had diminished in size to the short ‘Stiletto’ style of the Stuarts. By 1700 most men were going clean shaven.

On the surface, the virtually simultaneous decline of facial hair and rising popularity of wigs in the second half of the seventeenth century appears coincidental. Contemporary sources are frustratingly quiet on the nature of the relationship between beards and wigs. There were, for example, no fashion guides advising men to lose the beard and don the wig. One obvious conclusion is simply that there was no connection, and that fashions had simply shifted.

There were certainly similarities in terms of the prosthetic nature of both wigs and beards. Both could easily be adopted, put on and taken off at need. Both were manageable according to fashion, and both bore connections with masculinity, albeit in different ways. Why, then, did beards and wigs seem to be so incompatible?

One issue was simply the jarring aesthetic that the wig/beard combination created. Wigs and moustaches? Possibly. But wigs and beards, no. The wig was intended to contribute to a neat, elegant and harmonious whole – the goal of the polite gentleman. It was a fashion statement; one that shouted ‘status’ and rank. Later in the century there were complaints that wigs had sunk so far down the social scale that they were in danger of losing their potency as social markers. Facial hair, by contrast, had become seriouslyunpopular. In part this was because it came to symbolise roughness and earthiness, a component of the poor, country labourer, rather than the metropolitan gent. The two did not belong together.

Mixing beards and wigs also risked an odd clash between ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’ hair. Wigs were artificial contrivances. An individual removed their own ‘natural’ hair and replaced it with something fashioned from the frowzy hair of the poor. Conversely, as many authors had spent the previous two centuries arguing, beards were ‘natural’ – a God-given component of the male body. But men were increasingly having their beards scraped off, leaving the face clear. Perhaps part of the issue, then, lay in covering. Head hair was removed but the head re-covered by the wig. Beard hair, by contrast, was shaved, but not replaced. In this sense, the ‘site’ of masculinity shifted from the face to the upper head, with the head covered, and the countenance open.

A further possibility, although perhaps less plausible, was the so-called ‘cult of youth’ which, amongst other things, encouraged smoothness and softness of skin as aesthetic ideals. Beards, and even stubble, could be scythed off with a newly-fashionable steel razor, giving a man soft and smooth skin. He might even slather on some of the many pastes, lotions and oils that were coming on to the market in the eighteenth century. The wig, though, could contribute to the illusion of youth, by giving an apparently luxuriant head of hair.

Whatever the true reasons, the wig and beard were uncomfortable bedfellows. There are very few formal portraits of bearded men in the eighteenth century. Those that do exist are usually paintings of older men, for whom the beard was a sign of wisdom and experience, and sometimes Biblical figures. But, we would struggle to find a painting of a bearded and bewigged gentleman! Some things, it seems, simply do not belong together.

One thought on “Unnatural Fashions: Wigs and Beards in the 18th Century.”