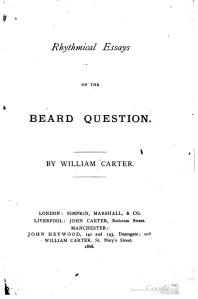

This is a transcript of the paper I gave at the BBC ‘Free Thinking’ Festival in Sage Gateshead, November 2014. Enjoy!

Something beardy this way comes! Love them or loathe them it seems that beards are everywhere at the moment. Walk down your local high street and before you’ve gone too far it’s a fair bet that you’ll be met by a veritable sea of hairy faces. In many ways 2014 may well prove to be the year of the beard. After a fairly long period in the wilderness, facial hair has returned. It may well have passed you by but there is actually a World Beard Day, dedicated to the celebration of the hairy chin. In Bath in September was held the British Beard Championships, a virtual X-Factor for beard-wearers, where owners of mighty examples of facial topiary submitted themselves to the scrutiny of a panel of pogonotomists. For whatever reason – and there are potentially many – beards are back.

How long can this last? Questions were beginning to be raised in spring 2013 as to whether ‘peak beard’ had been reached. This is the point at which some theorists think that beards become so ubiquitous as to render them unfashionable again. There are certainly no signs of change at the moment. Only a few weeks ago came the startling revelation that, in the past year, manufacturers of razors and related goods such as shaving foam, have seen a drop in sales of more than £72 million pounds. Market analysts IRI noted that men’s shopping habits were changing and, even though the total market still accounted for 2.2 billion pounds, this was a substantial dent. The cause of this change? Beards.

Not everyone is a fan. In fact, as Jeremy Paxman found out to his bewilderment, beards have the power to be extraordinarily divisive. Pogonophobia – the fear of beards – is apparently on the increase. What is it about beards that some people find so apparently distasteful? Some men – and women – just dislike the feel of beards. Most men can probably sympathise with the feeling, usually after the first week or so, that your beard is attacking your face with itching powder. Once that passes and some semblance of dermatological normality resumes there are the social problems to overcome. Small pieces of food lodged in a beard do not present a good look. So obsessed were the heavily-bearded Victorians with this problem that they invented all manner of devices and contrivances to cope. These included ‘moustache spoons’ to stop errant whiskers dipping into the soup course. Some people feel that beards are hiding something. There is, in fact, a long history of distrust. Henry VIII’s beard, for example, was allegedly extremely unpopular with Catherine of Aragon, who pleaded with him to shave it off. In fact, Henry’s emblematic beard was actually the result of a bet with Francis, king of France. Before their famous meeting on the field of the cloth of gold, both men resolved not to shave until the big day.

But the decision to wear or not wear a beard, moustache, whiskers etc is one that has long been a problem for men. Over time, attitudes to beardedness and, indeed, shaving have constantly shifted. Something so seemingly mundane as facial hair is actually bound up in a complex web of meanings. To paraphrase Karl Marx (a poster boy for the beard if ever there was one!) men don’t just act as they please; instead they behave according to the influences of the society they live in. Growing a beard is a conscious decision and can be for a variety of reasons from cultural to religious. In fact, although we’re concentrating more on other influences today, religion is very closely linked to beard wearing, especially for example in Judaism, Islam and Sikhism, and can even become a cultural stereotype. Some men might protest that they just got fed up with shaving…but the decision not to shave is an equally conscious one. However much we like to think we are all individuals, as a group we behave in predictable patterns. And, to be fair, we can’t blame the coalition for this one.

If we look back through history it is amazing how many periods have their own, immediately identifiable, facial hairstyles. In the Renaissance, for example, beard-wearing was a sign of masculinity and almost a rite of passage. To be able to grow a beard represented the change from boy to man. As the historian Will Fisher put it in his article on beards in Renaissance England, “the beard made the man”. It is noteworthy, for example, that most portraits of men painted between, say, 1550 and 1650 contain some representation of facial hair – from the Francis Drake-style pointy beard to the Charles I ‘Van Dyke’. The beard was viewed as a basic mark of a man, but this was not just something fanciful. In fact, beards were strongly linked in with theories of medicine and the body. Early modern medicine saw the body as consisting of four fluid humours – blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. Facial hair was regarded as a form of bodily waste, which resulted from heat in the reins – the areas around the genitals, and the liver. As such, beards were strongly linked to sexual prowess and fecundity. A man’s sexual capabilities were writ large across his face. Nevertheless, beards were still not for everyone. Some prominent figures such as Thomas More and Oliver Cromwell preferred the clean-shaven look in line with austere religious beliefs. Indeed, 17th-century Puritans, never a group in love with display, viewed the beard as an unnecessary bauble on the face. For men in this period, therefore, the beard was not just some frippery; it was closely linked the very essence of manhood, and concepts of health, sexuality and the body.

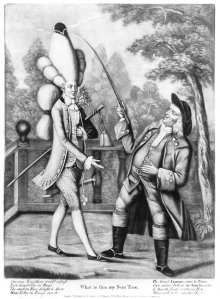

The eighteenth century had been one where men were almost entirely clean-shaven. Here it was in fact the lack of facial hair that defined the ideal man. The face of the enlightened gentleman was smooth, his face youthful and his countenance clear, suggesting a mind that was also open. This was the age of the fop and the dandy, where the very idea of growing a beard would have been greeted with a furrowing of the be-wigged brow and a few choice words about impropriety and vulgarity. Interestingly, this was also the first period in history when men began to shave themselves, rather than see a barber. New, sharper razors were accompanied by the first signs of anything like an advertising campaign by razor makers. Growing a beard at this point would only have been a deliberate act done purposefully to convey a message. John Wroe, for example, leader of the Christian Israelite group, let his beard grow wild to signify his withdrawal from society. In this sense beards, and their removal, were closely linked to technology and culture, and to the expanding world of enlightened science and innovation.

By the mid-Victorian period, however, the beard made a spectacular return to favour. Sometime around the 1850s, concepts of masculinity itself began to change. Something strange was happening to men in this period and they were under new pressures to reassert their authority and status. This was the age of industrialization which brought with it new challenges, not least in the need to create hierarchies and structures of authority to cope with the sheer numbers of men who could now work within a single company. But men were also increasingly nervous about women. If, as was beginning to happen, women were finding a voice and beginning to agitate for greater levels of independence, this would be a significant threat to the status quo. Men needed to react. And they did.

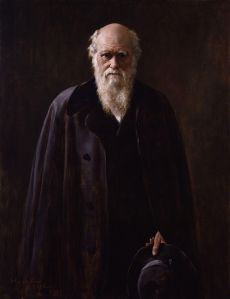

One of the ways they did this was to place a new emphasis upon the physical characteristics and strength of men. According to the new view, men should reflect what has been termed ‘muscular Christianity’. In came a new vogue for athleticism, sports and game playing. The underlying theory was, as EM Forster put it that sport encouraged ‘well developed bodies, fairly developed minds and undeveloped hearts’. Vigorous, vital and athletic men were exactly the sorts of stout fellows needed to swell the ranks of the army, and defend and expand the Empire. Whilst the connections might not immediately be clear, the beard played a strong part in this process; in fact, it virtually became the emblem of the Victorian man. Central to this was the belief that the beard was simply the ‘outward mark of inward qualities’ of masculinity, such as independence, hardiness and decisiveness. A man’s character and strength was visible upon his face in the form of a large bushy beard. A range of new sources stressed the scientific basis behind men’s ‘natural’ authority, alleging irrefutable proof that women were the weaker sex and should therefore know, and keep, their place. This was the age of Darwin, who argued that man was essentially the result of millions of years of evolution and natural selection. The beard was a God-Given marker of man’s ‘natural’ strength and fitness to be the dominant sex. Not only this, Victorian thinkers called on science to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that man had come to be the masters of the world simply because he was the best equipped to do it. How could women argue against the pure logic of science and nature and the morality of religion when the very emblem of masculinity was literally staring them in the face?

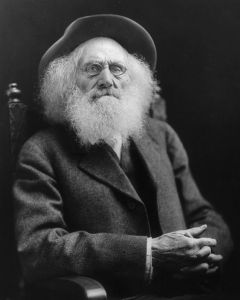

If Victorian men also needed new bearded heroes then they found a ready source amongst the ranks of explorers and hunters. This was the age of exploration, of hunters, climbers and explorers. As rugged adventurers began to tackle the terra incognita of far-flung continents, they would immerse themselves in wild nature, letting their beards run riot. The beard became a symbol of rugged manliness and men began to emulate their bewhiskered heroes. Albert Smith was the Englishman who went up a mountain and came down…with a beard. Smith was an author and entertainer but also a mountaineer who, in 1851, had climbed Mont Blanc. He was also the inspiration for the Victorian craze for mountain climbing. As a new exemplar of the mastery of men over nature, Smith personified the Victorian masculine ideal.

By 1850, however, beards were becoming valued not just for their cosmetic attributes, but their health benefits too – and doctors were beginning to encourage men to grow their facial hair as a means to ward off illness. As Christopher Oldstone-Moore points out, the Victorian obsession with air quality saw the beard promoted as a sort of filter. A thick beard, it was reasoned, would capture the impurities before they could get inside the body. Others saw it as a means of relaxing the throat, especially for those whose work involved public speaking. Some doctors were even recommending that men grew beards to avoid sore throats. Clergymen who shaved, according to one correspondent in the Hampshire Advertiser in 1861, invited all sorts of ‘thoracic and pectoral woes’!

For the Victorians, beards were closely linked not only to new ‘scientific’ ideas of male dominance and ‘natural’ authority; they also drew on age-old themes of the beard as the ultimate symbol of manhood. A Victorian man unable to grow some sort of beard was scarcely a man at all!

The twentieth century brought a variety of styles. In the first decades after 1900, moustaches were definitely in vogue. Part of this was to emulate the rugged masculinity of British military. It was in fact a military regulation that British soldiers must wear a moustache, until General Sir Neville Macready, who hated the moustache, repealed the order in 1916. The 1920s saw Chaplin’s toothbrush moustache achieve notoriety. Some speculate that a certain Austrian corporal Hitler actually took his inspiration from Chaplin, whose work he admired. In the 40s, bushy fighter pilot moustaches were all the rage, but the improved availability and quality of razors was making shaving easier, more comfortable, and increasingly popular. By the 1960s the beard was the ultimate symbol of the tuned in, turned on and dropped out hippy. Everyone from John Lennon to the Joy of Sex man was heavily hirsute and proud of it.

The 80s introduced designer stubble. This was the decade when razor advertising crossed into popular culture. Electric razor advertisements were full of speedboats, motorbikes and parachuting heroes. We also learned from Victor Kyam that the humble razor could be the inspiration to buy a whole company! The 90s gave us the goatee…about which, the less said the better!

But where once beard styles could last decades, the pattern in the past 10 years or so has been more towards months. That is why the endurance of the current crop of beards is actually quite interesting. Whatever the current, vogue for facial hair tells us about men today it is clear that beards, moustaches and whiskers are not just a quirky sidenote; in many ways they are in fact central to a range of important themes in history. One of the most constant of these has been emulation. In the early modern period monarchs provided a bearded (or indeed clean-shaven) ideal. By the Victorian period powerful and fashionable figures, and new types of industrial and military heroes, offered men something to aspire to. Now, with almost unlimited access to the lives of celebrities through the voracious media and internet, the opportunities to find ‘heroes’ to emulate are almost limitless. If history tells us anything it is that nothing stays the same for long. How long this current trend will last is difficult to say. What is more certain is that men’s relationship with their facial hair will continue to change and evolve, and provide us with a unique way to access the thoughts and feelings of men through time.