Much in the news of late has been the rising rate of suicide amongst men. Perhaps most surprising of all has been the dramatic rise in suicide amongst middle aged men, aged between 45-64 and has been noted in the USA as well as northern Europe. A recent UK government report lists suicide as the leading cause of death amongst British men aged between 20 and 49. In 2012 a cross government outcome strategy, assisted by major charities, was launched to address concerns about male suicide which are, as a recent article in the Guardian suggested, more than three times higher than for women.

According to the Samaritans one of the primary causes of suicide is the mid-life crisis. Many men are finding it increasingly difficult to cope with reaching 40 not having achieved the financial or family security that they expected, or with goals or dreams unfulfilled. But Clare Wyllie, Samaritans head of policy and research, also highlights a central problem for men, and one that has been a constant issue through time.

“Society has this masculine ideal that people are expecting to live up to. Lots of that has to do with being a breadwinner. When men don’t live up to that it can be quite devastating for them”. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/feb/18/male-suicides-three-times-women-samaritans-bristol

Ideals of masculinity – in a sense the ideal or model man – have changed dramatically across time. As men have adapted to changing conditions, fashions, cultural changes and shifting views about sexuality the boundaries of manhood have also changed. Accompanying this, however, has been a literature telling men how to behave. It might be argued that men, and perhaps especially young men, have long been in competition with themselves, encouraged to measure their behaviour against that of a perfect model of masculinity.

This was certainly the case in the early modern period. Of course I’m generalising here, and there were wide variations. But Tudor and Stuart men had to negotiate a minefield of expectations about their behaviour, appearance and, frankly, sexual prowess. In were manly sports such as wrestling and fencing. Young men were encouraged to sow their wild oats to some degree. In the 1590s Cambridge students indulged in all sorts of high jinks from drinking and carousing to tousing young women and, frankly, indulging in mild forms of violence. (See Alexandra Shepherd’s excellent Meanings of Manhood in Early Modern England) for more on this). While boisterous behaviour in young men was seen as natural, the more mature (and better off) might cultivate interest in fitting gentlemanly pursuits such as self-improvement and education.

But men had family duties to attend to. As heads of family and household they were required to govern and rule. The household was viewed as a microcosm of society, with the man required to guide his wife, children and servants as a kind but strict patriarch. In sexual terms men were expected to perform their duty in creating more Christians; one of the few reasons for which a divorce might be granted was if a man did not do his duty in the marital bed.

But there were also ambiguities. The same society that was paranoid about the heinous sins of sodomy and buggery also thought nothing of two men sharing a bed together or, in displays of courtly or fraternal friendship, kissing each other. Samuel Pepys makes several mentions of his ‘bedfellows’ . Snuggling up next to a friend was after all a useful way of keeping warm when travelling and staying in a cold room.

In some matters too, Tudor and Stuart men were on their own. Whilst advice literature provided them with a range of useful information, seldom did it give them much advice for such basic things as looking after the sick or basic domestic tasks, things that were traditionally the domain of women. What were they to do if their wife fell sick?

During the eighteenth century ideals of manhood were to change from a rugged masculinity and more towards an elegant and refined model. Georgian man was neat in his appearance, clean-shaven and elegantly, if not extravagantly dressed. Out went rough manners and brusque language and in came self-control, mastery and discipline – especially when addressing the ladies. In the company of delicate feminine creatures, men were extolled to moderate their language, be calm and civil and, overall, do nothing to offend the sensibilities of young women, to whom a poorly chosen word could raise a blush!

Lord Chesterfield’s letters to his son were subtitled ‘On the Fine Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman’, extolled the virtues of etiquette, clean living and sound morality. Even future US president George Washington had plenty to say about the ideal man. His list of ‘Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour’ included everything from keeping a pleasant countenance to not laughing too much in public, not eating in the streets and not revelling in the misfortunes of others. Above all, he cautioned ‘let your recreations be manful, not sinful. (see the full list here: http://www.ballindalloch-press.com/society/civility.html)

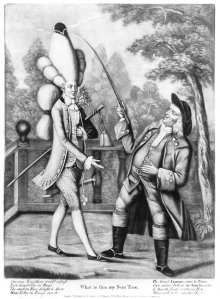

Nonetheless the often portrayed poster-boy of Georgian manhood, the fop or dandy, was definitely not the masculine ideal. Effeminacy (in the sense of appearing or acting like a woman) was severely frowned upon. Much ink and paper was expended by authors who complained about the immorality of modern dress, appearance and manners. Some feared that new fashions were rendering men too weak to be of any use in the country’s defence. How, they argued, could Britain defend itself against the gathering French hordes if its men paraded themselves around in wigs, breeches and face powder?

By the 1850s, the pressures and challenges of industrialisation brought yet more changes. Victorian man was stern, patriarchal and stoic. New masculine heroes, including explorers and hunters, as well as the new heroes of the technological world exemplified his spirit of adventure and sense of superiority over the female sex. In an age where women were increasing beginning to find a voice and press for new rights and powers, men needed to reassert their authority, and did so by invoking everything from religion to science to bolster their claims to superiority. Like Mr Murdstone in Dickens’ David Copperfield women and children were to be dominated and controlled. Weakness was derided. Anything smacking of sexual and emotional deviance was (if you follow Foucault’s line) to be punished.

What, then, is today’s model man? In many ways things are more complicated. A veritable barrage of heroes and anti-heroes assails men from every direction. Magazines such as GQ and Men’s Health tell men how to dress, how to look, what to eat and drink and where to see and be seen. The media daily creates and destroys new male models and icons. In sexual and emotional terms men are perhaps freer than they have ever been to express their identity, although many prejudices and limitations remain. The result of all this is a rather amorphous and indistinct model of the ideal man. Men are confused by what they should be. Indeed, the waters are further muddied by the wealth of advice literature, which tells men to plough their own furrow and forget trying to live up to unachievably high standards. There’s no easy answer to any of this, but the ever shifting ideals of masculinity through history remind us that nothing, ultimately, stays the same for long.

One thought on “500 Years of the Model Man!”